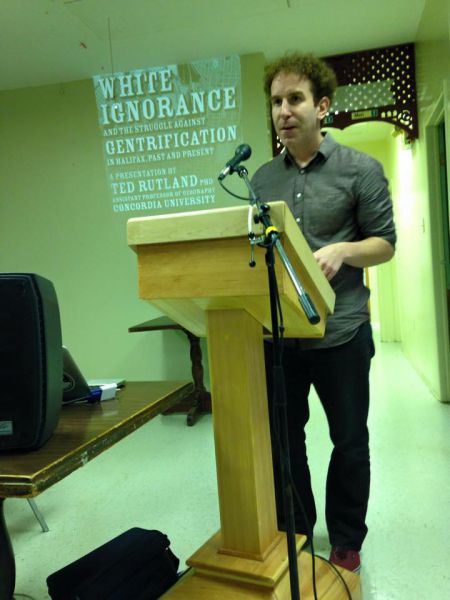

KJIPUKTUK (Halifax) - A talk featuring Concordia professor Ted Rutland on the history and politics of gentrification in Halifax easily filled the 250-seat Army Navy Club hall on Maynard Street earlier this week.

Rutland was joined by panelists Lynn Jones, Ingrid Waldron, and El Jones. The event was sponsored by the Radical Imagination Project.

Ted Rutland is an assistant professor in the Department of Geography, Planning, and Environment at Concordia University in Montreal, where his research focuses on the racial politics of urban planning, housing, and policing in Canadian cities.

Before delving into the past, Rutland painted a bird's eye view of the current state of "redevelopment, repopulation, and re-imagination" in Halifax's North End.

The stats are there. In the early 2000's the average price of a home between North and Cornwallis shot past the rest of Halifax for the first time in history, and then kept growing. Ten years later, the neighbourhood is seeing a development boom of both condos and commercial spaces that is transforming the neighbourhood.

The black population of the North End which made up 27% of the population in 2006, was down to 20% by 2011, according to stats presented by Rutland.

Gentrification is hardly a new phenomenon. "In Halifax, there hasn't been a moment when there hasn't been a claiming and a displacement process," said Rutland.

It started right with Cornwallis, who arrived here in 1749 with both a plan for a new city and a bounty for the scalps of Mi'kmaq people, said Rutland. "When we're talking about displacement, claiming and violence, that's the history of Halifax.”

Fast forward to the early 1900’s for another key moment in this history. A diphtheria epidemic, concentrated in poor neighbourhoods, leads authorities to demolish homes, and a well-intentioned plague of progressives 'help' people by taking control of their children, their houses and their neighbourhoods. The progressives are "people who want to do something useful, but have no idea how to do something useful," said Rutland.

Here's where the "white ignorance" of the talk's title finds its roots. It's a term coined by Charles Mills to describe a kind of "socially produced" ignorance, a huge blind spot to how others might be experiencing the world.

This lack of understanding extends through race and class, and leads to a frustrating paradox: "White people don't necessarily understand racism even though they are the ones perpetuating it,” said Rutland.

Luckily this ignorance can be reduced, said Rutland, “but we've got to recognize it.” Wednesday's discussion seemed like it scratched out a beginning in that process.

Rutland's history lesson didn't end with the 1900's. Most are at least somewhat aware of the takeover of Africville and the resettlement of former residents. But it didn’t begin or end there. The 50's, 60's and 70's saw roughly 5000 additional people displaced in Halifax's North End.

To the largely home-owning black community in the North End this was especially devastating. In addition to more sinister profit-driven motives, much of it happened under the well-intentioned auspices of 'progressive' urban renewal.

Rutland's final historical example was actually a failed attempt at dislocation. In the early 1970's as the tides were turning on urban renewal, protests by a number of community groups stopped the completion of Harbour Drive, a massive ring road that would have encircled the peninsula, destroying sections of the north end and much of the waterfront.

This time, Rutland pointed out, the good intentions behind the campaign reflected something different: a renewed interest in public space. The middle class were starting to value urban life again, and the idea of the lively, dynamic city is born. "It's a huge moment where we see a different way of being in public space," said Rutland. "And it's exactly that idea that creates gentrification."

In racist Halifax of the 70's through to today, the urban revival is not experienced the same way by everyone. It's a different city for anyone outside of the predominantly white and powerful middle class.

And, concluded Rutland: "The only way in which anti-gentrification politics is legitimate in this context is to prioritize the struggles of black communities against displacement."

After Rutland's presentation Dr. Ingrid Waldron spoke briefly, drawing on her recent research in Halifax's North End, and looking at gentrification as a process of racialization. "Gentrification is a highly raced, gendered, and classed phenomenon," said Waldron. "It reaffirms existing racial hierarchies, and consequently helps to sustain the social order."

"Recognizing white ignorance as a symptom of white privilege is about understanding gentrification and other processes of racialization in general," said Waldron, "including environmental racism, discrimination in the labour market, and everyday forms of discrimination."

Panelist Lynn Jones turned the night down a less academic route, and gracefully requested a new, less esoteric term for gentrification. El Jones offered up "The Takeover”.

Lynn Jones pointed out that the crowded room she walked into was filled mostly with faces she didn't know. "You need to understand," said Jones to the mostly white audience, "that the very things we're talking about–displacement, disenfranchisement, segregation–all those issues, it's really happening right here, too."

"Are black Nova Scotians the subject or object of this discussion?" she asked.

Panelist El Jones performed a series of poems, including one she had written in 2012 for a rally in support of the bid by the Richard Preston Centre for Excellence, the Mi’kmaw Native Friendship Centre and the North End Community Health Centre to take over the surplussed St. Pat's Alexandra school.

Just last month the Supreme Court of Canada refused to hear an appeal to contest the on-again-off-again sale of the school site to JONO Developments. So for now it seems the fight to keep the former public school as a community space is lost.

Perhaps the most compelling part of the night came as the mic was handed over to the audience.

Veteran, mostly black North Enders got up to share their experiences and thoughts on what's happening in their neighbourhood. Newer, mostly white North Enders got up to share how they came to be there, and to express support. An aboriginal speaker pointed out the irony in having a white keynote speaker.

“We are not a phase,” said one speaker. “We were here before it became cool, and we’ve had to be here. So If you want to be part of our community, that’s fine, but recognize what you’re being part of… I don’t expect you to understand what it is to be of colour. You can only see through your own eyes, but you need to listen and listen well.”

Another speaker described “the heart of Halifax”, Creighton Street. “Creighton was a large indigenous black community. Most of us were homeowners…. We had a large, close knit and culturally strong community. We were here, and we have no intentions of going, and we’re fighting back for our houses.”

The problem of jobs came up more than once. One speaker whose daughter had to leave Nova Scotia to find employment as a lawyer, lamented, “How come my only child can’t be here with me?”

“If you want to be welcome in our neighbourhood you should be more kind, more inviting, and give our children jobs,” she said. “The summer is coming…”

“It’s important to acknowledge that there’s no one way to fix this issue,” said another audience member. “When we’re up here and have the opportunity to talk it seems like this tsunami of issues,” but “we can tackle these one by one.”

“It starts with kinship, with approaching people in public, making eye contact. This is your opportunity. If you leave this room without making contact with a POC person, then you shouldn’t have been here.”

“If we’re going to stand with our brothers and sisters who are dealing with this all the time, you think we’re not going to feel it?” asked another speaker. “No, I’m sorry, we’re going to have to feel it.” And feel it for the long haul. “Because there’s no way to win unless you’re in it for the long haul.”

Organizer Max Haiven left feeling optimistic. The night was a "tentative good first step," he said.

It felt like a beginning to a long conversation, the kind we'll need to have over and over again.

Listen to a recording of this event here.

Online discussion of the event is happening on Facebook.

You can follow Erica Butler on Twitter @habitatradio