To truly compel, in any fictional work, a good character must have a certain flaw or weakness, an Achilles Heel if you will. How the character deals with the weakness, whether internal or external, will determine the heights to which they will rise, or the depths to which they will fall. Superman had his kryptonite, Samson his haircut, and on and on.

In the non-fiction world of politics, a would-be leader is often groomed to the point where such character flaws are ironed out by handlers, spin doctors and the like. Too many obvious flaws or skeletons in the closet going in, and the would-be leader is necessarily screened out by so many political filtration devices. Hence, sometimes, the plastic and unpalatable feel of our political class. Rare is the outburst or the public breakdown, and if ever they are put on display, the perpetrator of the unscripted emotion is often shown 'Exit Stage Left'.

How rare the occasion when we see the fears, the weaknesses, the 'Aha!' moments, of our political class.

So it was with great interest, through the often mundane action of filing Access to Information Requests, that the Halifax Media Co-op has obtained documents that suggest that former Premier of New Brunswick David Alward and his office shared a distinct fear of meetings with the province's Indigenous people, when held in traditionally-styled long houses.

I have searched, and I do not believe there is a proper, medical, diagnosis for the fear of meetings in traditional long houses. Longum Domum Phobia would be the most direct Latin translation, but perhaps something gets lost, as it so often does, in translation.

To clarify, in mid-November, 2013, in protest against the provincial government's continued push for shale gas exploration and development, St. Mary's First Nation Chief Candice Paul, along with the Traditional Maliseet Grand Council, erected a traditionally-styled long house in a grassy field beside the New Brunswick Art Gallery, in downtown Fredericton, the province's capital city. The long house was across the street from, but in direct sight of, the provincial legislature, where the provincial government was sitting.

By this point in mid-November, scores of New Brunswickers had been arrested in protest against shale gas exploration activities, which were localized in Kent County, New Brunswick. Shale gas exploration, as we know, leads to shale gas development, which requires the water-intensive and environmentally-damaging technique known as hydraulic fracturing, or 'fracking'.

Inflaming 'on the ground' tensions in November, key members of the Mi'kmaq Warrior Society remained imprisoned after a hundreds-strong Royal Canadian Mounted Police raid upon their encampment took place on the morning of October 17, 2013. Many perceived their imprisonment as politically-motivated, rather than objectively representing any notion of Crown-style 'justice'.

Cross-Canada solidarity actions had taken place with those protesting shale gas in New Brunswick. Activists across the country had temporarily shut down key highways and ports, and state surveillance of such activities had reached a heightened state.

The need for dialogue between the New Brunswick government and Indigenous representatives from the protest, towards defusing what had become a volatile situation, was fairly obvious to all those interested in a peaceful resolution to the situation. The possibility of an anti-shale gas insurrection, localized in certain areas of Kent County, was not out of the realm of possibilities. Certainly, a social breakdown, directed specifically at members of law enforcement, had taken place.

Towards the hopes of a resolution, a meeting between the six Maliseet Indian Act Chiefs of New Brunswick, the Traditional Maliseet Grand Council, and then-Premier and Minister of Aboriginal Affairs David Alward was requested by the Chiefs. Readers know, of course, that traditional Maliseet territory extends west of the Saint John river, which runs north-south and splits the province of New Brunswick roughly in half.

The meeting place, as requested by the Chiefs, would be the newly-built long house in view of the front facade of the legislature.

Accompanying this request was a resolution, dated October 24, 2013, signed by the six Maliseet Indian Act Chiefs, along with then-Grand Council Grand Chief Harry Laporte. The resolution, addressed to then-Premier Alward, then-Minister of Energy Craig Leonard and SWN Resources Canada – the company engaged in the shale gas exploration work - demanded a moratorium on shale gas exploration and development within the province of New Brunswick.

According to a series of emails we have obtained from the Premier's Office, while the resolution was accepted and acknowledged by the Premier (although exploration work would nonetheless continue), the meeting itself was problematic. It wasn't necessarily that Alward would not meet with the Chiefs – he had done so in the past. No, apparently the meeting request itself was a problem, due to the fact that it was meant to take place within the long house outside the Legislature.

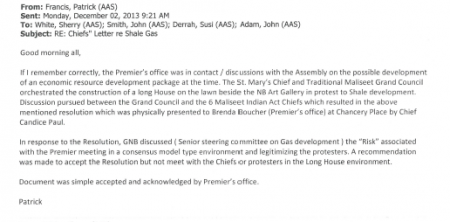

An email from New Brunswick's Deputy Minister of Aboriginal Affairs, Patrick Francis, dated December 2, 2013, reads as follows:

“The St. Mary's Chief and Traditional Maliseet Grand Council orchestrated the construction of a long House on the lawn beside the NB Art Gallery in protest to Shale development. Discussion pursued between the Grand Council and the 6 Maliseet Indian Act Chiefs which resulted in the above mentioned resolution which was physically presented to Brenda Boucher (Premier's Office) at Chancery Place by Chief Candice Paul.

In response to the resolution, GNB discussed (Senior steering committee on gas Development) the “Risk” associated with the Premier meeting in a consensus model type environment and legitimizing the protesters. A recommendation was made to accept the Resolution but not meet with the Chiefs or protesters in the Long House environment.

Document was simple (sic) accepted and acknowledged by Premier's office

Patrick”

It is not clear who sat on this “Senior steering committee on gas Development” alluded to by Francis. By this point in the campaign to 'frack' New Brunswick, so many such strange and bureaucratically named committees and groups existed that keeping track of who was meeting with who, under what banner, in charge of what corner of governmental power, becomes almost an exercises in futility. There were risk assessment committees, shale gas committees, even the RCMP in New Brunswick had their own 'Shale Gas Unit'.

In any case, to be even more clear: It wasn't the lack of electric lighting, or the dirt floor, or the oncoming winter's chill, or even the possibility of getting ash stains from an ever-burning fire onto their coats, that the Premier's Office feared of the long house.

No.

According to Francis' email, what they feared most of all within the long house was the concept of the “consensus model” and all that that might entail.

Putting the kibosh on a meeting of great importance, while at the same moment sections of highway in Kent County burned in rage against shale gas exploration, while arrest tolls mounted, all over the concept of “consensus”, is something that quite frankly boggles this reporter's mind.

Was not David Alward Minister of Aboriginal Affairs? Was not Patrick Francis, Alward's deputy minister, a Maliseet and a former Chief of Tobique First Nation? Was defusing this situation not part of their job description?

For clarity on this, I defer completely to newly-appointed Grand Chief of the Maliseet Grand Council, Ron Tremblay.

“The only thing that I could think of, why Alward wouldn't want to meet in that type of environment is that he might have feared that he'd be viewed at possibly accepting our way of government, the traditional way, where it's based on nation to nation governance,” says Tremblay. “Maybe he was informed that our treaties were signed in pretty much that type of format and that possibly, by coming to our longhouse, that he would recognize our system. Then, that would show that he recognizes the Grand Council and that our treaties are legal and valid.”

“By him coming to that longhouse, it would show that he agrees to meet with us on our terms, rather than how he was used to running that show.”