“[Correctional officers] ... look right through me and say nothing. They just look right through me like I am not standing right in front of them.”

– Black inmate, quoted in the 2013 Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator

While Aboriginals and women, because of special or statutory considerations, often receive a structured response to their needs, African Canadians do not.

ACPAC's response to the Annual Report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator (OCI), released by the federal government in late November 2013, confirms the need for stronger action to address this disparity.

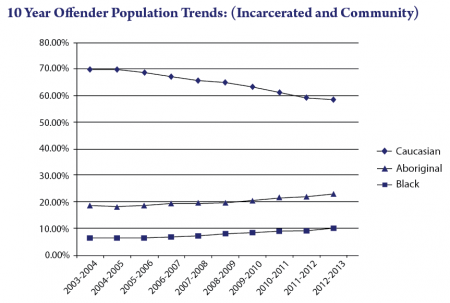

The OCI report found that there has been an 80 per cent increase in federal incarceration rates of African Canadians over the last ten years.

In his report, Correctional Investigator Howard Sapers states that not much has changed in prison conditions since the infamous riot of Kingston Penitentiary inmates in 1971, resulting in two deaths and the destruction of much of the prison:

Many of the same problems that were endemic to prison life in the early 1970s – crowding; too much time spent in cells; the curtailment of movement, association and contact with the outside world; lack of program capacity; the paucity of meaningful prison work or vocational skills training; and the polarization between inmates and custodial staff – continue to be features of contemporary correctional practice.

Sapers concludes that “this environment is particularly difficult on the growing complex needs (of) populations in corrections."

ACPAC says the report doesn't address “the urgent crisis” of mental health issues for African Canadian inmates, even though the coalition developed an extensive literature review on the subject.

Robert S. Wright is a member of ACPAC. He has worked with black inmates in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and has been a Correctional Mental Health Specialist at Washington State Penitentiary.

ACPAC members from Ontario and Nova Scotia were approached by OCI to conduct a review of the literature on mental health issues facing African Canadians, Wright says.

Their hope was that the report would come up with substantial recommendations. It did not.

Wright says he's happy about the case study in the report, which examined the African Canadian experience in prison – with special attention to a literacy activity where black inmates were asked to read racist statements as part of a discussion group on Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn (The book was subsequently replaced.)

The report also states that discrimination has moved from more overt forms, like racist language, to more covert and subtle forms, like ignoring and shunning.

Cuts to prison chaplains, the ban on calling cards to allow foreign nationals to call home more cheaply, and overall lack of culturally appropriate programming affected black inmates especially, the report noted.

Sapers made two recommendations: one for a National Diversity Awareness Training Plan be put in place, and the other for an Ethnicity Liaison Officer position to be created.

Wright, however, felt these recommendations were generic and insufficient.

“Aboriginals and African Canadians are facing a crisis in prisons. Aboriginals have a particularly tailored response [because they have a special status]. African Canadians need a particularly tailored response as well.”

ACPAC recommends stronger anti-racism policy and training and more specific research on the mental health status of blacks in prison.

In Canadian federal prisons, inmates first spend time in a classification unit to determine where they will be housed – minimum, low, medium, or high security. “Administrative segregation,” like protective custody in American prisons, is where inmates who have either a high risk of being perpetrators or victims are housed.

These inmates spend more time locked in cells and don't get to leave unless with an escort or in segregated groups.

African Canadians are more likely to be classed high risk, Wright says. They don't get to the parole board as quickly as other inmates, despite the fact that blacks have lower recidivism rates. Sapers' report affirms this:

Despite being rated as a population having a lower risk to re-offend and lower need overall, Black inmates are 1.5 times more likely to be placed in maximum security institutions where programming, employment, education, rehabilitative and social activities are limited.

This is a structural problem, Wright says. Why?

“Because we don't understand the life of a black guy living with poverty or racism on paper,” he says. He offers an example: while someone diagnosed with depression or anxiety might be eligible for treatment, a person who has anger management problems might be subject to discipline if it's chalked up as a personality issue.

In his words, “the glasses by which we look at cases are not socially informed"; addictions, mental health, and education programs are not culturally specific.

So, what needs to be done?

Federal corrections “needs to host a national conversation with black leaders, federal corrections, provincial and territorial mental health specialists” in conversation with OCI and the Canadian Human Rights Commission.

“Anything else would be a reaction; we need a coordinated, organized, funded national conversation to develop a structured response. From arrest and conviction to reintegration, we need to develop richer resources” to meet the reality of black inmates, he says.

“In a society where blacks have been oppressed, poorly served by the education system, and poorly served by the mental health system, .... they are overrepresented by the prison system,” he says.

The HMC spoke with ACPAC in December. A response from community group Ujamaa is forthcoming.