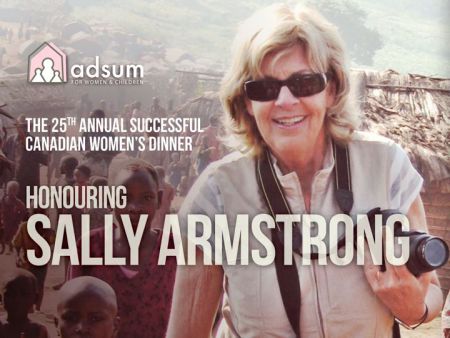

After decades of reporting on the plight of women in war zones and the developing world, Sally Armstrong sees a positive trend in the status of women globally. And this Thursday Haligonians will get a chance to hear from Armstrong herself about this shift, and the women that are behind it, at the 25th annual Successful Canadian Women's Dinner in support of Adsum for Women and Children.

Halifax Media Coop's Erica Butler spoke to Sally Armstrong to ask about her work as a journalist, and the thinking behind her positive outlook for the women of the world.

HMC: You started out at Canadian Living Magazine, moved on to edit Homemakers Magazine, and you've won several Amnesty International Media awards for articles published in Chatelaine. How is it that you came to bring stories of women in conflict zones and developing nations to the pages of Canadian lifestyle magazines?

Sally Armstrong: A couple of decades ago when the all-news networks started to come into our living rooms, Canadians started to have a longer glimpse at what was happening in the world. As a woman, when I saw these 90-second truncated news reports about women being ill-treated, about ethnic cleansing, about the kinds of things I thought were appalling, I wondered if the readers of Homemakers felt as I felt. I didn't have a budget for research, so I simply wrote to 300 readers, and they wrote back. When my readers said they were as concerned as I was about the issues we were now seeing on all-news channels, I decided we would see what we could do with it as a magazine.

HMC: When you wrote about Bosnian women being raped in camps in the 1990's, you had originally thought that was a hard news story that should go into the news system. But it didn't end up there. Tell us how that happened and do you think it would happen differently today?

It would be very different today.

I was in Sarajevo doing a story on the effect of war on children. The day before I was to leave, I began to hear rumours about rape camps. All day long I kept hearing them from more and more credible sources, and by the end of the day I knew there was something to it.

But I was working for a magazine. I could race this headline story to press in about 3 months. So I knew it had to go to a news place. I gathered everything I could, names, addresses, phone numbers, anecdotes, and I flew out the next day. I landed in Toronto and I took it to a news agency. I said to the editor, give this to one of your reporters, this is an incredible story. And he said yeah, he would.

I waited seven weeks, and didn't see anything. Then I saw a 4-line blurb in Newsweek saying women were being gang-raped in rape camps in the Balkans. I phoned the editor and said, what happened? He said it was a good story, and I was going to assign it, but I got busy and I was on deadline, and you know, I forgot.

I thought, 20,000 women were gang raped, some of them 8 years old, some of them 80 years old, and he forgot? I was furious. So I went back to my office and I told my staff. They said we should do it, and I said, we can't get it to our readers for 3 months. They said, so?

I was on a plane two days later and I went to do that story.

The lesson, though, is that I didn't get that story because I was smarter than other journalists. I got it because others didn't want it. Sarajevo was stuffed with journalists. Everyone would have heard the same rumours I heard.

Today if that happened, coming from Homemakers Magazine I would be in a long, long line up. I would be way behind CNN and BBC and CBC and everybody else. That's the difference today. Now women's issues are on the front page.

HMC: Your newest book is called Ascent of Women. Despite the horrific stories you've collected and documented over the years, you say that women are turning a corner. What's behind this conclusion?

I knew the earth was shifting under the status of women. I could tell. But I worried that it was wishful thinking on my part. So I did the research, and I found out I was right.

The women's movement, as you and I know, was very much a Western women's movement. Asian women and African women weren't particularly caught up in it. But with the rise of Islamism in the 1990's, Asian women began to realize they'd become the targets of extremism in their own religion, and they had to take action because they were in danger. They formed groups.

Then in Africa, with the HIV/AIDS pandemic racing through the continent, women were telling me that they had no right to say no to sex. And they said if we don't get together and take on the impunity of men when it comes to sex, we'll all be dead. So they started forming groups.

Now we've got Asian women, African women, Western women all forming groups. But I knew that wasn't really it.

You know what did it? Facebook. Once Facebook came out you could see all the data tracing right back to it.

What happened was women around the world–north, south, east, and west–started talking to each other. And when they talked to each other, they found out who lives how. Women in Afghanistan said how come you live like that and we don't live like that? And they started asking questions they'd never asked before. They started questioning the doctrines that they were stuck with. And women wearing hijab found out that despite what the fundamentalist tells them, women wearing jeans were not whores after all. And women wearing jeans found out that women wearing hijab had many important opinions that had to come to the table. That they weren't subjugated, oppressed and silent.

So it was when the women started to talk to each other. I dare say that was the worst day in the lives of fundamentalists and extremists and misogynists.

HMC: Tell me about the group of women and girls in Kenya who are suing their government for not taking more steps to prevent them from being raped. What happened with them?

It's so exciting, they won. They won it for 10 million girls in Kenya. And the fall out to that has been extraordinary.

You can't just change the law, you have to retrain the judges, the lawyers, and the police. And then, you have to increase publicity. You have to make the public more aware of those changes. You will not succeed unless you follow those steps.

So right now in Kenya they're trying to retrain the police. And it's moving along very well, very rapidly.

I'm going over there in November to do the story on how that is changing things. Winning the case was fabulous, but that wasn't going to change the way girls were treated in Kenya overnight. And it would never change it, until the police were retrained, and the lawyers and the judges. And that's already happening.

HMC: And what about the situation of women in Canada? More and more we are realizing that there's a frightening level of violence being leveled at aboriginal women and girls. Do you see any hope there?

That is a national disgrace. So is the polygamous cult in Bountiful, BC. So is the fact that our shelters are stuffed with women who had to leave home because they were being beaten by their husbands. This is a national disgrace. And again, if you can't talk about it, you can't change it.

I've just been assigned a story about Aboriginal women and I'm very excited about doing it because I did one about eight years ago and it pointed out the whys and the wherefores, but it didn't get any traction. We have an ability to look the other way, and somehow we have to get the public of the nation to pay attention to these issues.

We're not at the finish line in Canada, any more than they're at the finish line in Afghanistan or Kenya. The difference is we have infrastructure. We have an operating judiciary. We should be able to move rapidly to the finish line.

HMC: You've written that based on your experience reporting over the years, you've found women are more interested in fair policy than in power, and in peace rather than a piece of the turf. Does that conclusion still hold true for you?

Absolutely. Go anywhere and you'll find that's true. Go to the community centre and you'll find that's true. Go to the United Nations and you'll find that's true. Go to the Parliament and you'll find that's true.

HMC: Is that why numbers of women in Canadian parliament are still so low?

We have increased. Not a lot, but we have increased. What you need in a place like a parliament is a 30% representation in order to change the culture. Right now I think we're at almost 26%. It's not enough, not nearly enough.

It used to be a woman couldn't get elected because the parties only gave women the un-winnable seats to run in. It used to be a women couldn't get elected because she didn't have enough money. I don't think those are the issues today.

Nobody's talking about it but I dare say one of the issues today is women look at what goes on in the House of Commons and they cannot picture themselves taking part in such a playpen. I think a lot of women find the conduction of politics abhorrent. And who's going to do that job when we are losing respect for the way the job is done?

HMC: Who stands out for you as epitomizing this ascent of women that you describe in your work?

I couldn't pick just one. I think of some of the big personalities. Geena Davis is fantastic. Eve Ensler. Gloria Steinem. These are huge names in the world who are coming out for women. Hillary Clinton–she's outstanding with the work she's doing for women.

But then I think of Sima Samar in Afghanistan. I think of Farida Shaheed in Pakistan. I think of Siphiwe Hlophe in Swaziland. The women I interview on the ground, in the midst of the crisis, you know, their stories they play on the back of my eyelids. I have such admiration for them.

I think of a little 6-year-old girl in Afghanistan saying to me she wants to be President of Afghanistan when she grows up.

Those little girls in Kenya who were raped. I'm thinking of Emily, only 11 years old, such a tiny kid with this husky voice that sounded like Walter Kronkite. She'd been raped, for godsakes, by her grandfather. But she was empowered because she was doing something her mother, her grandmother, her great-grandmother never dared to do. She was taking them all on to make a better life for herself. And she won.

I feel very humbled that they tell me their stories. I feel very grateful that I get to know them. I feel like a very lucky journalist.

Sally Armstrong will be speaking in Halifax on Thursday October 23rd at the 25th annual Successful Canadian Women's Dinner in support of Adsum for Women and Children.

Follow Erica Butler on Twitter @habitatradio