Learning that kiln-baked sewage sludge, also known as 'biosolids', is being marketed and sold across Nova Scotia as fertilizer, came as a shock to Lil MacPherson. MacPherson owns 'The Wooden Monkey', a Halifax restaurant that emphasizes local, seasonal, and organic ingredients.

“I'm out there, trying my best, through the restaurant, to promote local foods, and promote sustainable agriculture,” says MacPherson. “Then all of a sudden I get this news, that we're using seriously toxic sewage sludge spread throughout Nova Scotia, which eventually goes through our food system, and I was horrified.”

MacPherson was troubled that much of Halifax didn't know what happened to their waste once it went “flush”. Looking to plunge Haligonians into the light, she and long-time friend Ellen Page are staging an event coined 'The Nova Scotia Soil Conference', on March 13th at Pier 21 in Halifax.

The purpose of the conference is to discuss whether HRM's baked sludge is safe for soil application, of any kind. A wide range of speakers will be on hand, including internationally renowned microbiologist, and US Environmental Protection Agency whistle-blower, Dr. David Lewis, as well as President of Minas Basin Pulp and Power, Scott Travers. Travers is slated to discuss the potential for energy extraction from sludge.

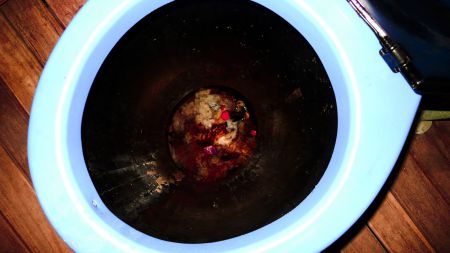

Sludge is the substance that falls to the bottom of a settling tank in a waste treatment plant, and human fecal matter is just the tip of the sludge-berg. Sludge from a typical city's sewers can, and often does, contain heavy metals, pharmaceutical residues (excreted traces of the drugs that so many of us ingest on a daily basis), hospital waste, as well as an array of substances termed by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment as 'Emerging Substances of Concern'. ESOCs include personal care products, flame retardants, and musks, to name but a few.

Fighting alongside MacPherson, and also slated to speak at the March 13th conference, is Jason Hoffman. A former Iowan cattle farmer, Hoffman has a PhD in plant physiology and biochemistry, and is now a compost consultant in the Halifax region. He advocates extreme caution when dealing with sludge, and certainly doesn't recommend using it, whether cooked or raw, as fertilizer.

“The problem is not with the human excrement itself,” says Hoffman, “it’s everything else. Although even if you were just dealing with the human excrement, you still have the not inconsiderable problem of pharmaceutical residues...and the scale is huge. [The] drug industry assumes no responsibility for that aspect of it.”

Hofman also warns of the practice of applying biosolids to pasturing lands, a practice which is endorsed as safe for Nova Scotia's biosolids.

“I know how cows eat grass. They get a mouthful and they pull it up and there’s often a lot of dirt hanging on that.” says Hofman, explaining one of the ways that biosolids can enter the food system. “So it’s a direct ingestion problem. Then there’s the whole question of fat-soluble accumulation in the milk. The dairy people ought to be very concerned about that. (Milk products) is the last place you want to put biosolids.”

“Not everybody buys into the notion that what we put into our drain ends up back in our food chain. People just can’t make that connect because we are disconnected from how our food is grown,” says Marilyn Cameron, also slated to speak at the conference, and chair of the Biosolids Caucus of the Nova Scotia Environmental Network. “It’s going to take a long time to restructure society and get us to be more responsible for what we put down our drains.” says Cameron.

Cameron notes that in the meantime, there are technologies for processing sludge that are “absolutely incredible.”

One of those technologies is the Canadian-developed, and internationally renowned PASO (Plasma Assisted Sludge Oxidation) system, which uses a plasma torch to oxidize the water trapped within the sludge. Heat energy, which can be potentially captured and used, is released as a by-product. Hydro Quebec developed the technology, and Fabgroups, a Quebec-based company, has signed a licensing agreement to develop, manufacture, and market it. Fabgroups has set up a test PASO system in Valleyfield, Quebec, and has been entertaining big-time investors from stateside.

“Basically it reduces [sludge] to sand-like crumbs,” says Ted Mulhern, director of business development for Fabgroups. “Typically you have a twenty-fold reduction in volume.” Jean-Paul Gendron, Coordinator for Water and Environment for the city of Valleyfield, notes that their PASO system reduces Valleyfield's 8000 metric tons of sludge to 900 tons of end-product.

“At a plant at full capacity,” says Mulhern, “with an oven that can handle four and a half wet tons of sludge per hour, you're generating at about twelve million btu per hour. That translates into about 3.5 Megawatts of thermal energy every hour [and the system is] designed to run 24/7."

According to Mulhern, that's enough energy to power a conventional waste treatment plant, typically a city's largest energy expenditure, with enough energy left over to feed the grid. Given Nova Scotia's current fixation on coal of questionable origins, sludge-derived power may not be so far-fetched.

“It has great potential to generate alternative forms of energy at a very low cost,” says Mulhern. “Typically your cost of producing electricity is at about 4 cents a kilowatt, so it's a very interesting technology.”

While the test plant in Valleyfield is not set up for energy-capture quite yet, Fabgroups is preparing to install this key piece of technology in the near future.

But while Valleyfield and other communities look towards the future of waste management, Nova Scotia remains knee deep in its own sludge.

Since 2008, Greater Halifax’s sludge has been handed over to a company called N-Viro Systems Canada LP. N-Viro, whose facility is located in Aerotech Park, near the Halifax Airport, adds a hearty dose of cement dust into the mix, and bakes the whole mess in a kiln.

The end product is trademarked as N-Viro Soil, and is sold across Nova Scotia as a Canadian Food Inspection Agency-approved fertilizer. CFIA seal of approval notwithstanding, critics, including Hofman and Cameron, claim that applying N-Viro Soil to the Earth is introducing a mysterious mix of potentially harmful ingredients right into the soil.

A recent study by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME) found that a plethora of pharmaceuticals were turning up in survey samples of N-Viro Soil. ESOCs with proven cancer-causing track records, such as Bisphenol A, were also present.

“The problem as I see it is that this material just has too many contaminants.” says Hoffman. “When you look at the CCME study, the findings are in nanograms, which is parts per billion. And it’s very easy to dismiss any one of these compounds individually. But collectively there are thousands and thousands. Doing what? We know not.”

Hoffman also takes issue with N-Viro's addition of cement kiln dust into their end-product.

“What they try to do in Nova Scotia,” explains Hoffman, “because we have acidic agricultural soil, is...promote [cement kiln dusts’] ‘liming’ aspect. Cement kiln dust comes with its own basket of ‘what’s in it?’ and that needs to be looked at.”

The Canadian Horticultural Council (CHC) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), the very agency that licenses N-Viro Soil as a fertilizer, agree. The CHC and CFIA developed the 'Food Safety Program', which is a series of guidelines that large-scale produce buyers, such as Sobeys and Loblaws, utilize when selecting growers to supply their stores with produce. The Food Safety Program does not allow for Canadian produce-growers to apply municipal waste, N-Viro Soil included, onto crop-growing soil.

“The concern...is with possible chemical contaminants to the biosolids,” says Heather Gale, national program manager of CanadaGAP, a program linked to the CHC.“That might be things like pharmaceuticals or even something like personal care products that might get concentrated in the waste.”

N-Viro, for its part, claims that N-Viro Soil is safe for crop application of all kinds, and that it has the science to prove it.

“The only place that [N-Viro Soil] is not being applied to agricultural crops is fruits and vegetables in Canada. Nowhere else in the world.” says Lise LeBlanc, of LP Consulting Ltd, speaking for N-Viro. “And [N-Viro] is going to re-debate that, because [N-Viro] recognized that it’s not based on science. It is based on what most scientists call the 'yuck factor.'”

The 'yuck factor', or 'wisdom of repugnance', is not why CHC has rejected N-Viro Soil, says Heather Gale. Gale says they have seen N-Viro's science, and they aren't impressed.

“So far”, says Gale, “N-Viro has not been able to provide the information that our technical working group is looking for that would put their mind to rest around it.”

For the moment, only N-Viro knows where the N-Viro Soil goes. Marilyn Cameron has filed a freedom of information request for a list of N-Viro's customers, but has yet to receive it. In the interim, Cameron has collected the signatures of over 400 Nova Scotia farmers who have made the promise to never apply biosolids to their land.

MacPherson, in setting up 'The Nova Scotia Soil Conference', and in her buying practices at The Wooden Monkey, is showing solidarity with those farmers.

"Biosolids is not for 'The Monkey'", says MacPherson, "and we don't support that. We support and focus on buying from Nova Scotia farmers, and we will not buy any products that are grown using biosolids. Biosolids is not about recycling, it's just pollution transfer. It's not for the future of farmers in Nova Scotia, and we are supporting the farmers that are taking a stand with us."

The Nova Scotia Soil Conference is slated to begin at 9am, March 13th, at Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.