“To err is human, to forgive divine”

– Alexander Pope

As twilight filtered through the stained glass windows of St. Matthews United church, those gathered for a public lecture on forgiveness leaned closer together to discuss four stories about making peace.

A public lecture and discussion on forgiveness and restorative justice was held Sunday at the St. Matthews United Church on Barrington Street.

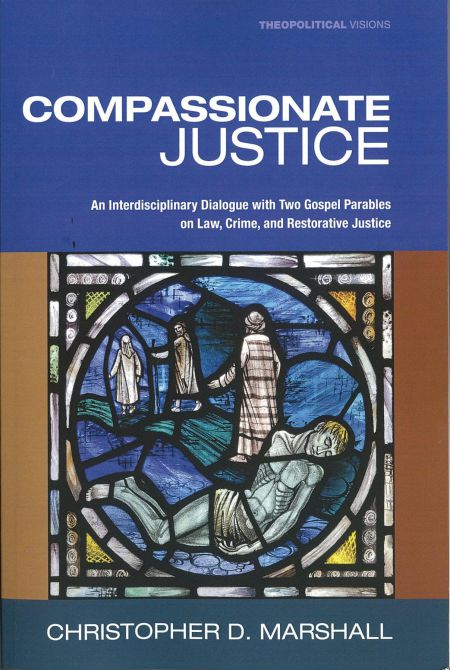

Professor Christopher D. Marshall is visiting Halifax from New Zealand, where he is the Chair of Restorative Justice at Victoria University in Wellington. He is a trained and accredited restorative justice facilitator who has published seven books and more than 100 articles and book chapters.

“Even using the f-word often touches an emotional nerve in people,” he told the crowd.

To say “Will you forgive me?” is much more powerful than saying “I'm sorry,” he said. The obligation to forgive is often seen as denying a victim's right to anger, grieving, and resentment – but often forgiveness is the most creative act in a relationship. Just as forgiveness seeks to repair a relationship, restorative justice is about restoring a sense of justice among parties.

Marshall gave the example outlined in the book Amish Grace, which chronicles how the Amish community expressed forgiveness toward the family of the 32-year-old gunman who opened fire in a Pennsylvania school and killed six people, including himself. Marshall raised this radical prospect: What if the Amish were in charge of the War on Terror, offering forgiveness to those behind the 9/11 disaster?

Within the context of political crimes, memory is still important, but the point of forgiveness is not to memorialize in anger, Marshall explained.

He also spoke of Eva Kor, a Holocaust survivor and a twin. As a child, she survived Joseph Mengele's experiments and eventually extended a hand of forgiveness to the Nazis who killed her family.

Why did she do it? To free herself: “I immediately felt a burden lifted from my shoulders. I call forgiveness the modern miracle medicine ... I was no longer a victim."

Sister Pat Wilson, Community Chaplain at the Halifax Community Chaplaincy, works with men and women who are coming out of the correctional system. She also works with families and victims.

A former offender wants to talk with the victim three years since the crime occurred, she said: in her eyes, that alone is a success in a path toward healing and reintegration.