K'JIPUKTUK (HALIFAX) – How would you spend $94,000 to better your community?

That’s exactly what Councillor Jennifer Watts asked residents of her Peninsula North district.

The councillor handed over $94,000 in discretionary funding for the community to decide what non-profits to support in the neighbourhood.

Rather than make decisions behind closed doors, participatory budgeting allows residents to vote for projects they believe will have the greatest impact in their community, Watts said in an interview Wednesday.

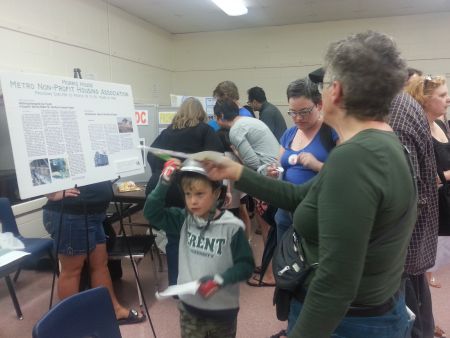

More than 600 people flowed through the doors of the Bloomfield Centre to cast their vote in the north end’s first participatory budgeting process Wednesday night.

“I’m frankly overwhelmed,” Watts said.

“Something is striking a chord here that people want to participate in decision-making,” she continued. “They want to be informed and they want to be able to have an impact on things that are happening in their community.”

Projects ranged from new playground equipment to bike stand repairs, site renovations to musical instruments.

In the end, Ward 5 Neighbourhood Centre, The Africville Heritage Trust Society, Army and Navy Air Force Veterans, Needham Daycare, Progress in the Park, Wee Care Development Centre and Metro Non-Profit Housing received funding.

Douglas MacDonald, director of Ward 5, says the $20,000 the centre received will go towards the first phase of a playground redesign project that will give kids in the north end a safer, more exciting place to have fun.

Located next to the the North End Day Care Centre, the playground sees up to 70 children a day and has been a valuable part of neighbourhood for the past 40 years, he says.

The money will also help cover the costs of removing a tree that is growing through the middle of the playground’s basketball court.

“It’s a bit of a job,” MacDonald says.

Participatory budgeting was first introduced in Halifax by Councillor Waye Mason in his Peninsula South Down district two-years ago. And it was the community aspect of the program that Watts says first caught her attention.

How the process works is simple: non-profit organizations set-up a science fair-type display so residents have a chance to walk around and ask questions about the different projects before they vote.

“Sure you could do (voting) online, but people really need to come out,” Watts says. “What’s happening here, right now, is that people are connecting with people. It’s invaluable.”

Her philosophy of, “anybody that can hold a pencil can vote,” was made to give both children and their parents a chance to learn about civic participation and take part in their community’s decision-making.

Watts sees education as one of the most important benefits of the participatory budgeting, since it allows people to learn about different projects that they maybe didn’t know were happening in the neighbourhood.

“They might have come out because they want to support one (project), but they have to vote for five.”

MacDonald agrees, saying the event provided non-profits with a “fantastic networking opportunity.” He’s thrilled to have received funding, but believes the whole process was worth it either way.

“They’re having an amazing opportunity to talk about their work to people who they will otherwise never connect with,” Watts adds.

Each organization had a $20,000 cap for funding in order to give money to as many projects as possible.

But it wasn’t a loss for those organizations that did not receive funding. Watts hopes many residents left with an impression, and will choose to support the projects they didn’t vote for in more creative ways, such as by donations or becoming a volunteer.

She sees it as a win-win situation for everybody.

“I can’t see any way of not doing it next year.”