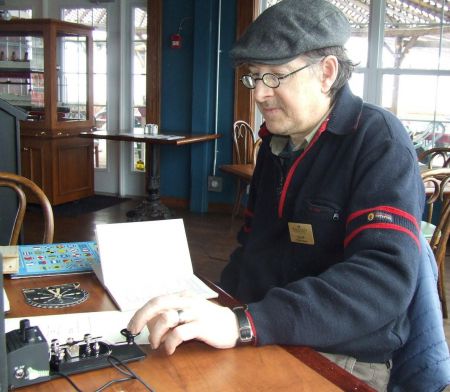

About 50 people gathered at Murphy’s Cable Wharf restaurant yesterday for the official launch of an exhibit celebrating Halifax’s role in a 19th century communications revolution. The revolution began in 1858 with the laying of the first transatlantic telegraph cable. It meant that messages, which took weeks and sometimes months to cross the Atlantic by ship, could now be transmitted within hours by telegraph operators hammering out the dots and dashes of Morse Code.

“There’s a historian who said that the laying of the transatlantic cable was in some sense the Internet of the Victorian age,” said John Hennigar Shuh of the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic. “This is an incredibly important part of our heritage. It’s something that we should be celebrating.”

The exhibit consists of 10 panels erected on the wharf outside the restaurant at the foot of George St. The panels tell the stories of how Halifax ships and crews played a vital role in maintaining and repairing 3,000-kilometre-long transatlantic cables that frequently broke or corroded. One panel calls the transatlantic cable “The Eighth Wonder of the World” because “international communications were transformed forever.”

"Tough old tars" fixed cables

“It’s worth keeping in mind that one thing that is special about this wharf is we think of this as a technology and as an instrument for communication,” says Dan Conlin, curator of Maritime history at the museum. “But behind it were all these mariners, these legendary captains and tough old tars who actually went out to fix cables when they broke. There were generations of these men who earned a good living doing this and this was their home.”

The first stage in laying the transatlantic cable involved establishing an underwater cable link between Newfoundland and Aspy Bay, Cape Breton in 1856. A successful link between Ireland and Newfoundland was established in 1858, but the cable failed within a few weeks. However, Conlin says the cable paid off for the British government.

“The British were fighting the Indian Mutiny and the fighting was going badly and they sent a message in a mailbag to Halifax that took weeks to get here saying, ‘Send the two regiments in Halifax to India.’” Conlin adds that the British general who had Trollope St. named after him, had hired ships and was loading supplies when word arrived in London that the Mutiny was over.

“In the old days it would have been too late. Those guys would have sailed all the way to India for nothing, but the cable had just been completed. So they sent one message to Halifax that said, ‘Keep the troops there. Don’t spend the money to send them.’ And that one message paid for the British government’s investment in the entire cable.”

After several more tries, continuous cable service was successfully established in 1866.

“People really believed this technology would make the world smaller, turn us into a global village, eliminate international misunderstandings, usher in an era of peace and education,” Conlin says. “Doesn’t that sound like everything you’ve heard about the Internet?”

He adds, however, that the transatlantic cable, like the Internet, had its drawbacks.

“It enabled generals to fight wars much faster. It enabled con artists to really cheat people and criminals were very quick to adapt to cable technology, much as they were able to adapt to the Internet.”

Cable and the information age

“It’s all about the information age,” Colin MacLean, president of the Waterfront Development Corporation told the gathering at Cable Wharf yesterday. (The exhibit is a partnership between the WDCL, Murphy’s restaurant and the Maritime Museum.) MacLean referred to one of the panels, which points out that transatlantic cables could transmit only about eight words a minute while today’s undersea fibre-optic links can handle one hundred million messages simultaneously.

“I’m very sorry to say,” MacLean added, “that our panel is already out of date.” He noted that the US company, Hibernia Atlantic, had just announced plans for a second undersea cable running from Herring Cove to the U.K. that will carry almost one billion simultaneous phone calls.

“So, already we have to change the panel when we haven’t even unveiled it yet,” he said. “Such is the information age.”