Last Thursday, residents in Saint John, New Brunswick, attended one of many planned open houses for the proposed TransCanada Energy East pipeline.

Kathy McNulty felt uncomfortable with how the meetings were conducted. “There's no give and take between us and the employees,” she told the CBC. “I felt really managed by the company. And I mean that in the least complimentary way.”

She's not alone in her discomfort. Environmentalists and indigenous activists are questioning the politics around the $12-billion TransCanada Energy East pipeline – what in their circles is known as “Bitumen East.”

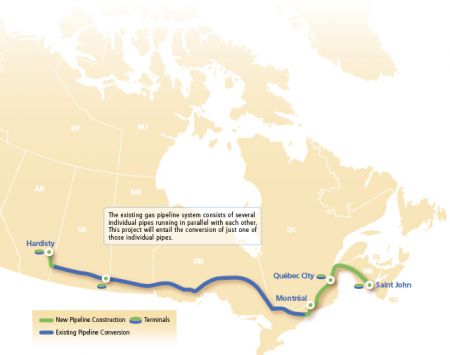

The proposed oil pipeline is meant to bring tar sands oil from Alberta to refineries in eastern Canada, and end at the Canaport LNG terminal, a deep water marine terminal in Saint John.

Industry proponents claim the pipeline will bring energy security to Atlantic Canada while touting the construction as a nation-building project. Opponents see a sticky substance most Eastern refineries are not built to refine. For them, this project means placing communities and waterways at risk so that Alberta's landlocked crude might reach off-shore global markets.

The pipeline would transfer 1.1 million barrels across the country a day. This is twice as much as the maximum possible consumption of oil in Eastern Canada. Currently Atlantic Canada refineries rely on imported oil from overseas sources – mostly Nigeria, Libya, and Saudi Arabia – and export their surplus production to the United States.

Alex Pourbaix, the TransCanada Corp. executive in charge of oil pipelines, told the CBC that foreign oil costs $30-40 more per barrel. TransCanada CEO Russ Girling has predicted that the global demand for crude will rise by 10 to 30 million barrels/day in the coming years.

Cat Abreu works at the Ecology Action Centre in Halifax, and is convinced that renewable energy will create a more sustainable local economy. She believes the emphasis on national energy security is misplaced, as the pipeline will move Alberta oil to Eastern refineries but also foreign markets such as India. “(The pipeline) is not about energy security, it's about exports,” she says.

Atlantic Canada already produces its own oil for export. “If the concern is about energy security, we should be using the oil we have here,” she adds.

Some of the oil would be light crude, which the refineries in Saint John could technically process. But most of it will be bitumen, a heavy unrefined product that no refinery east of Montreal currently has the capacity to refine. “Trying to go after Alberta oil – why would we take on the risks associated with the pipeline when we have local sources for energy security?” asks Abreu.

After the initial phase of construction, only about thirty long-term jobs would be created in the Atlantic region, mainly at the deep water terminal in Saint John.

“It's nothing compared to what could be created by a thriving renewable energy sector and energy efficiency market,” says Abreu. Domestic energy sources include wind, solar, tidal, and small scale hydro. The money and jobs generated from such resources come from and stay within the region.

Irving Oil has committed to this terminal but has said nothing about the refinery upgrades that would be necessary to process Alberta crude. For Abreu, this indicates they are concentrating on export markets, rather than local processing for local markets.

Irving Oil, which operates the refineries, did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

* * *

Matthew Abbott, a Bay of Fundy specialist with the New Brunswick Conservation Council, worries about the possible two- or three-fold increase in oil tanker traffic in the bay known for having some of the highest tides in the world.

Abbott hails from Charlotte County, which sits on Passamaquoddy Bay, where livelihoods are tied to the sea – as is true of most of the coastal areas of the province. The bay boasts an active lobster fishery and scallop fishery. The peninsular town of St. Andrews relies on wildlife and whale watching for jobs.

He acknowledges that some mitigation strategies are underway: shipping lines have moved to prevent ships from striking North Atlantic right whales in their customary waters.

To their credit, Coast Guard agencies take oil spill exercises very seriously, he says. But once oil is spilt, it's hard to reverse the damage – especially to something as unreversible as the reputation of pristine waters known for their seafood. Oil spreads quickly and doesn't mix well with local environments. Jobs reliant on the ecosystem are lost.

Abbott points out that TransCanada doesn't disclose all chemicals and solvents used to ship product extracted from the oil sands. It's unclear if the soup of chemicals mixed in with oil will float to the surface, making it relatively easier to clean if – or when – a spill occurs.

There are measures to mitigate the risks, but activists like Abbott do not find them earnest in in the absence of a meaningful renewable energy plan. Marine life is already threatened by ocean acidification and temperature changes occurring as a result of climate change.

“We're bent on consuming fossil fuels as quickly as possible, without regard for the major impacts of them on our world's ecosystems,” reflects Abbott.

Drivers in Eastern Canada currently pay a higher price to fuel their cars than their counterparts in the west. Pipeline proponents say Alberta oil should be cheaper.

But Abreu thinks that once the oil reaches foreign markets, that argument won't hold up. “As soon as they can ship to the Bay of Fundy (for export) than the story being sold to us is no longer relevant. That story being, 'if we can buy cheaper and refine it here, (oil) will be cheaper,” she says.

It's an outstanding question in the whole debate.

* * *

Civil groups like Greenpeace and the Council of Canadians have vowed to mount political campaigns against Energy East, but First Nations chiefs have reportedly been more cooperative-minded.

When David Alward, the premier of New Brunswick, threw his political weight behind the project in late July, he promised that “First Nations will be consulted every step of the way.”

TransCanada CEO Russ Girling promised the same.

Following Alward's support, the Assembly of First Nations Chiefs in New Brunswick (AFNCNB) issued a statement saying the pipeline must satisfy their concerns before it moves ahead. They called for protection of: the environment, the ability to exercise aboriginal and treaty rights, and the meaningful participation of First Nations in the management of any pipeline and all benefits arising from it.

Kevin Christmas, an independent Mi'kmaq activist who identifies as a “grassroots treaty activist” and a “peacemaker,” told the Media Co-op that the AFNCNB statement was meant to meet the industry halfway. He says the chiefs are mitigation-minded rather than looking to issue a prohibitive, preemptive “no.”

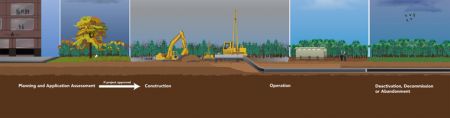

TransCanada will seek regulatory approvals in 2014.

The pipeline is slated to move oil by late 2017.

The project entails a conversion of the existing 3,000 km of “Canadian mainline” or natural gas pipeline (which composes 70 per cent of the proposed new pipeline), plus construction of new pipeline from Alberta to Manitoba, and again from Montreal to the refineries in Saint John.

In an email to the Media Co-op, Dalhousie law professor Dr. Meinhard Doelle wrote that “in light of recent changes to the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA), the environmental assessment (for the pipeline) would likely be carried out by the National Energy Board.”

The National Energy Board website makes the following statement regarding its assessments:

Regulated companies must implement mitigative and preventative measures for all risks posed by hazards and threats to the integrity of pipeline systems, the public and workers. The NEB expects those it regulates to use a risk-informed approach and focus resources on areas of highest risk to safety, security and the environment.

“We must step back from negotiating mitigation until the question of a preemptive 'no' is addressed. (The chiefs) are interested in getting paid for the process. They've already made those decisions without consulting us,” he says.

On August 15th, the AFNCNB voiced more explicit concern over the construction of the $300-million deep water marine terminal, due to its potential impacts on Aboriginal fisheries in the Bay of Fundy. Assembly chiefs have expressed good faith in Alward and Girling's promises of consultation.

But the grassroots movement has nothing in common with the chiefs, says Christmas, who has been organizing with the Sacred Fire resistance to shale gas exploration in Kent County. The Grand Council – the traditionally spiritual governing body for all of Mi'kmaqi – listen to the counsel of their lawyers more than the counsel of their own people, he adds.

“We have to create a voice before one is provided for us,” he says. “I know voices are being quieted – it's called quiet title.” The federal government negotiates with the First Nations chiefs in a manner which creates an environment of “non-assertion” – for Christmas, that means that Aboriginals “agree not to use our rights in exchange for something else.”

Despite environmental and regulatory reviews, legally, there is no way to say “no” to industry in Canada.

“There's no agency, nobody that has the authority to restrain anybody, especially corrupt politicians.” Existing regulations are constantly neglected, he adds. Even professionals have to lower their own levels of tolerance by misreporting or under-reporting industry violations.

In October of last year, former TransCanada engineer Evan Vokes made national headlines because he raised concerns over the competence of pipeline inspectors. TransCanada fired him in May 2012.

The court remains the only avenue from which concerned individuals can challenge the pipeline – but prior to construction, potential litigants will be told they are too early if there are industry promises to mitigate damages.

“Mitigation means equating your own title to a pile of dirt,” says Christmas.

Indigenous groups have the right to say no to any project that impedes on their aboriginal and treaty rights, which must be treated the same as private proprietary laws, he says. Treaty law stipulates that if Aboriginals should desire a court of civil judicature to deal with industry or individuals which make “false claims” to their land, it should be established for them.

In 1928 Gabriel Sylliboy was charged for trapping muskrats out of season, but the judge in his case ruled that he was in the right according to treaties and rights enshrined in the 1763 Royal Proclamation. “If (those rights) existed in 1928, they sure as hell exist in 2013,” says Christmas.

“We must use our treaty to reconcile title,” he adds. “We must make our treaty right ring with a no.”

“Bitumen coming here is the end of a faulty transaction to begin with. We're throwing out environmental oversight in favour of mitigation.”