The Nova Scotia chapter of ACORN, a national organization of low and moderate-income families, is asking for the reinstatement of rent control in Nova Scotia.

At a town hall held at the Halifax North Memorial Public Library on Thursday, organizers asked tenants to make it an election issue.

Co-founder Evan Coole argued that rent control is the most cost-effective way to ensure affordable housing. Provinces with rent control determine increase based on a combination of inflation, costs, and/or fixed rate. Alberta, Saskatchewan, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland do not have rent control.

Premier John Savage's Liberal government exempted residential properties from rent controls in 1993 to the reported elation of the Investment Property Owners Nova Scotia landlord lobby group. Vacancy rates in the city were at 12 per cent in parts of Halifax at the time.

Ten years later and with a shipbuilding contract on the books – poised to bring many workers to north-end Halifax and Dartmouth – vacancy rates are low and rent is climbing.

Jonethan Brigley, 26, said his landlord tried to claim rent increases going back a few months without having served him a formal letter. He said the increases were beyond the shelter allowance afforded by the income assistance on which he depends to rent an apartment he shares with his girlfriend in north-end Dartmouth.

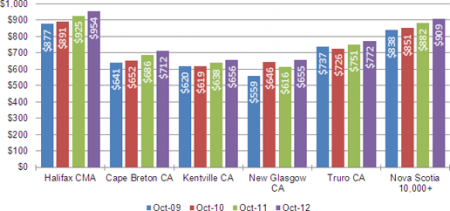

The average rent for a two-bedroom unit in Halifax is $965 per month, according to a Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) report. Rent has steadily risen at an average rate of 4.7 per cent each year over the past five years.

In April 2013, the CMHC reported that vacancy rates had settled at around three per cent in the HRM, on par with the national average. Darrell Dexter's NDP government never revisited the issue of rent control.

Three landlords are running in the upcoming election on October 8: two for the Liberals, and one for the Progressive Conservatives. Coole urged tenants to phone the provincial candidates in their ridings to bring back rent control if elected, passing around an open letter for those gathered to sign.

Brigley identified housing as his most basic political concern in the upcoming election. Though he's not inclined toward any candidate, he says that “if any party brought this issue up, they'd have my vote.”

Landlords can hike rent by any amount, only once a year, and must give their tenants four months' notice.

Bruce Muir, a legal student at Dalhousie, identified some of the flaws in the Residential Tenancy Act that weaken tenants' rights.

The act should be reformed to allow tenants to file a collective complaint, he said – though the act, as it is, shouldn't stop people from organizing together.

“If (tenants) could work together, they could pool resources with people in the apartment and have a better chance of winning ... If there is a universal problem, only those who come forward might get a remedy,” while others might be wronged, he said.

Although tenants can choose to mediate their dispute through the Residential Tenancy Board, at Small Claims, or the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia, tenants cannot appeal to the highest court in the province – the Nova Scotia Court of Appeal.

Muir said human rights issues should be decided at the highest level of court.