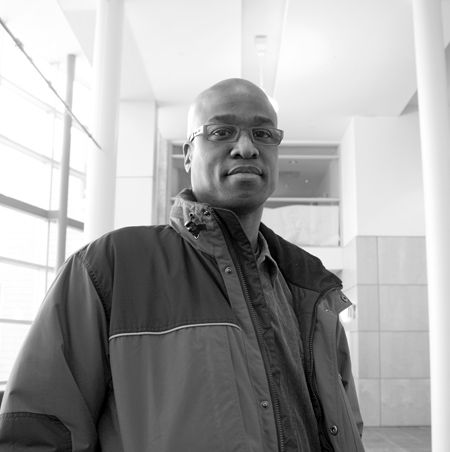

Too many times, 44-year-old Anthony Stewart has walked past one of his colleagues on Dalhousie campus only to face a blank stare from the other professor.

“There would be this moment when you would half lock eyes and there would be nothing there. No glint of recognition,” he explains, describing one such encounter with a fair-haired male colleague. “He would basically look right through to the back of my head like I wasn’t there. He wasn’t ignoring me; he just didn’t recognize me.”

Stewart, a tenured English professor at Dal, says it’s because most of his colleagues don’t expect to know anyone who looks like him: “tall, black and male.”

“It’s not really this person’s fault. Because of what this person does for a living, being a university professor, having gone to graduate school, this person just does not expect to know a lot of people like me.”

Stewart is not telling this story to draw attention to himself. A blank stare from a fellow professor doesn’t ruin his day. To him, it’s about larger implications.

“I’m not pointing it out just to be malicious or just to make them feel guilty or just to put them on the defensive, but because it matters and it means something. If that’s a blind spot in their perception and I notice it, then any of the kids they teach who superficially resemble me, those kids notice it too.”

Stewart’s concern is for the Dal community. He says universities, especially this one, are keeping minorities out of teaching positions. And at the same time, students are suffering the consequences of a prejudiced system. He explains this premise in his most recent book, You Must Be a Basketball Player: Rethinking Integration in the University.

Stewart has attended university since 1983, first as a student at Guelph, then at Queen’s and now as a professor at Dal. During this time, people have stereotyped him as a basketball player. He says the examples are countless.

Outside a library where Stewart had gone with a friend to hear professor David Divine speak, a white woman approached him.

“You must be a basketball player,” she said.

His friend’s mouth fell open in shock. Stewart had told his disbelieving friend just moments before that this happens to him frequently.

“No,” Stewart said, looking down at the woman from six feet, six inches. “I’m an English professor at Dalhousie University.”

“Good for you,” she replied sincerely.

For Stewart, the persistent assumption that he must play basketball has become a symbol for the struggle of minority groups within the university system.

In his book he uses anecdotes, told bluntly in first person, to highlight similar situations where students, colleagues or complete strangers have leapt to assumptions about him. As before, these anecdotes are meant to shed light on the bigger issue.

“If you major in English, history or philosophy at this university, among the full-time professors, the only professor you’re going to get who’s a person of colour is me.”

There are five black people, including Stewart, out of 130 staff in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences.

“Right now, the sort of unstated set of beliefs is that every white guy who works at a university is here because he was the best and the rest of us are here because of the benevolence of some other white guy, basically.”

When he began to write his book three years ago, he discussed this idea with professors from other faculties who belong to minorities. There is a clear consensus among them that prejudices exist within the university. But when he talked to faculty members who belonged to the majority, he found most were oblivious to the idea that Dal might have hidden prejudices.

In his book, Stewart says the reason minorities aren’t hired into teaching positions is because of preferential hiring. A problem he addresses in the book is one he calls the “benefit of the doubt theory.”

He starts by clarifying that most prejudice does not take place at the level of policy. It takes place when individuals make decisions.

Imagine a job interview where two candidates are vying for a position as a professor. One is a black woman with an ethnically marked name, the other a white male, “with a name like Anthony Stewart,” he jokes.

Both candidates do OK in the interview, but not great. They are on equal footing in terms of qualifications.

“As people are thinking about whom to choose between them, she doesn’t look like anyone who has taught them, she doesn’t look like anyone they’ve taught, really, and she doesn’t look like a whole lot of people that they know. He does. He looks the part already. At that point it would be very easy for her to be characterized as not being ready for the job and him being characterized as just having had a bad day.”

So when university administrators make that decision, which candidate do they hire?

“I’m here to tell you,” Stewart says solemnly. “Eight or more times out of ten, he gets the job. Because he reminds you of somebody.”

It happens for the same reason Stewart becomes “invisible” to his colleagues on the sidewalks of campus.

“It’s not volition, it’s not intent, it’s not malice. It’s practice.”

Stewart says he isn’t laying blame, because that would end the conversation he hopes to foster. Instead, his book brings the flaws of the university mentality into an unflattering light while simultaneously offering solutions.

“When people talk in terms of systemic discrimination, a lot of what is systemic is a collection of decisions made by individuals. So there’s blame to go around, but once you start talking in terms of blame people stop listening to you. I’ve tried to keep a measured tone in the book because I want people to read it, I want people to think about the issues.”

Stewart is not optimistic about change in university policy, although his book aims to cultivate it.

“Irrespective of intent, the effect is the same,” Stewart says. “If the place you work in looks like an exclusive country club, then it doesn’t matter whether you don’t want it to look like an exclusive country club. If it does, then some people are going to see it that way and some people are going to react to it that way. They’re not going to feel that they’re welcome there because they don’t feel welcome at exclusive country clubs.”

Stewart is confident a shift in policy will come when a critical mass of people want something done. He says it’s unfortunate, but universities work that way. He would know.

“I’m an insider. I’m a university professor. I’m not somebody railing at the gates yelling about how I’ve been kept out.”

Anthony Stewart's book, You Must Be a Basketball Player, is available at Outside The Lines on Quinpool.

This article can be found in its original format here: http://www.dalgazette.ca/?cmd=displaystory&story_id=3014&format=html