“We achieved a tentative agreement in the wee hours of the morning.” Said Kim Power, national representative for the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union of Canada, the union that represents Farmer’s dairy employees.

The previous day, the tone was much different.

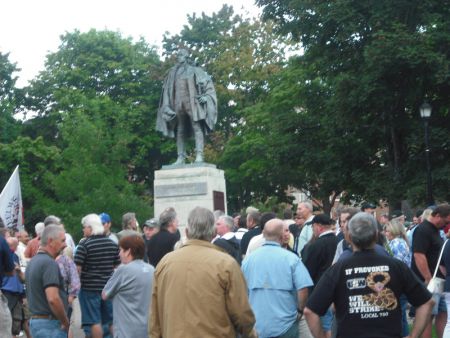

“I couldn’t eat my cereal this morning,” Said Gaétan Ménard, Secretary-Treasurer of the CEP, addressing the rally at Cornwallis park who had amassed for the August 18th rally.

He waited a couple of beats until the crowd, made up of an assortment of different unions, made sense of the apparent non-sequitur.

“Because the hotel I’m staying at uses scab milk!” The crowd riled up once more with cries of “scab” and “shame.”

Among the roughly 300 people in the crowd were representatives from various labour organizations; the Canadian Labour Congress, the Halifax-Dartmouth labour council, the Public Service Alliance of Canada, United Steelworkers and members of CEP 40N; the union of Farmer’s dairy employees who work inside the processing plant in Bedford, as well as the truck driver who transport the products. The workers have been off the job since July 10th.

Talks broke down between management and the workers on July 7th when management refused to agree to the union’s wage proposal. The union says that the same wages were given to the Farmer’s employees in Newfoundland, and they’re entitled to the same benefits. The breaking point, though, were management’s proposed pension cutbacks.

Once both sides walked away from bargaining, the workers filed strike notice, having rejected the previous contract, and the management locked the union out in an effort to pressure them into accepting it. The workers argue that the management initiated the dispute, while Farmer’s says the opposite.

According to the management at Farmer’s, the strike notice was filed before the notice of lockout and therefore the union is to blame. The Nova Scotia department of labour wouldn’t comment on the language of the dispute, and isn’t sure what happened first.

The two sides agree that both notices were filed within minutes of each other. Power says it doesn’t really matter which was filed first.

“Serving notice doesn’t mean you walk out,” she said. While notice was served, the approval for strike action had not taken place, and the walkout would not have occurred for at least another two days. The lockout notice, however, was immediate.

“If the employees didn’t leave ... they could have been arrested for trespassing.” Power explained.

“[The management at Farmer’s] locked the door then tried to convince the public and their shareholders it was a strike.” Said Rick Clarke, president of the Nova Scotia Federation of Labour.

The details of the tentative agreement won’t be released until sometime after the members vote on the proposal, which is taking place on August 20th. The workers, however, will stay on the picket line until an agreement has been accepted by a majority of the members.

A contentious issue during the dispute has been the use of replacement, or scab, labour while the unionized workers have been off the job.

“Lockouts and pickets are a fact of life, but it needs to happen on a fair playing field,” said Clarke, who called on the province to enact anti-scab legislation. “There are too many laws in this country [designed] not to help the workers but to help employers.”

It’s more than just principal, the workers argue, it’s also about public safety.

"We don't know who's making the milk in there. They're taking people off the street, we don't know if they're professionals," one worker told Global Maritimes.

According to Farmer’s, the workers were non-union employees who already worked in the building.

“Some of them were management,” said Power. “But our members do not recognize these workers crossing the picket line ... We don’t know where they came from.” Power indicated that there were also advertisements posted by Farmer's looking for temporary workers.

"We have products that are going into schools and hospitals ... where is the department of health? This is a public safety issue,” Clarke told the crowd.

Farmer’s disputes this, saying the replacement labour is well trained and the work being done is up to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency Standards. A source in the Food Agency said an inspection was done, and there appeared to be no decline in quality.

Regardless, the union is encouraging a boycott of all Farmer’s products. In some grocery stores, the fridges are full of Farmer’s milk, perhaps evidence that people are supporting the union and not buying the milk. While some businesses that rely on the company’s ice cream and milk say their supplies are running low, others say there has been no disruption in business.

Another issue that has been highlighted by the striking members is the use of Farmer’s “Made Right Here At Home” slogan, which they say is misleading. Some of the company’s products, such as their coffee cream, are packaged at the Gay Lea plant in Toronto.

The dispute may be coming to an end soon.

“As of last week, the issues were resolved.” Said Andrea Hickey, manager of Marketing and Communications, who expressed curiosity as to why the rally was held regardless of the progress made in the talks.

The union, however, still had strong words for Farmer’s. “I have a message for management; your expiry date has passed.” Said Clarke.