I would like to introduce you to three species you will never meet, each of them living out their final days sometime in the last 150 years, run to extinction for their fur, their feathers or their meat.

The reason I’ve picked these three animals is because we have records of our very last encounters with each of them, before they disassociated themselves from us and slipped silently into extinction. I am stirred by these records, the dates on which humanity parted ways with these animals we exploited into oblivion. It’s a reminder of the irreparable damage we’re capable of.

The first of these animals was unique among Atlantic Canadian fauna, an animal which favoured the rocky shores and islands of our great coast from Cape Cod to Labrador. Its fur shone red and it resembled animals like the otter and the mink. It was twice the size of its closest relative, the American Mink, measuring 83 cm by the most generous historical estimates. It was said to be slim and long legged like a greyhound.

The sea mink, they came to call it. Hunting began in earnest for these coastal dwellers in the 1700s, fetching a high price in the fur trade. It was the success of these hunts that prevented us from learning much about the sea mink. It was a strange sight to the first Europeans to come across it because of its appearance, but thereafter its value was only measured in fur.

To the best of our knowledge, the very last sea mink was killed on Campobello Island, New Brunswick, in 1894. I was unable to learn the circumstances of its death, whether the poor creature was trapped accidentally or if its death was exacted by a rifle, but I suspect it died for its fur.

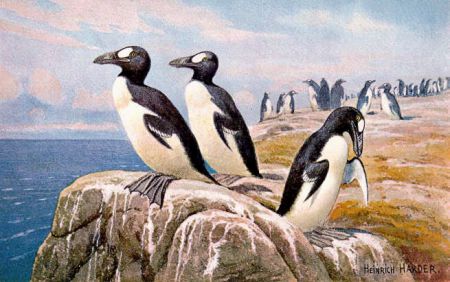

The next animal on our list was a flightless bird which made its living on select shores across the Atlantic Ocean, ours being one of them. They also called Greenland, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, Ireland and Great Britain home. It was called the great auk.

Although it shared a striking resemblance to the penguins of Antarctica, these two black and white birds were in no way related. In fact the great auks were called penguins long before their lookalikes on the South Pole inherited the name. Great auks were also called spearbirds or spearbill, making reference to their formidable beaks.

Of all shorebirds, the great auk took to ocean living most of all. It used its stubby wings as powerful flippers for cutting through ocean water in pursuit of fish, diving as deep as 100 metres. When on land, they stood taller than a man’s waist.

The great auk had a long the sustainable relationship with aboriginal communities across Atlantic Canada, but the demands of early industry proved more than this ocean lover could afford. Where once they nourished numerous communities with their meat, suddenly they were hunted for their feathers, for the oil rendered from their fat and for their eggs. They vanished in Europe, then in Canada, then Greenland.

Finally, on June 3 of 1844, three Icelandic fishermen came across the last two great auks we would ever encounter. These auks were a nesting pair, guarding their single egg. The fishermen killed them and found the egg was damaged, the last unborn child of an extinct species.

The last victim in this sad procession is the passenger pigeon, which occupied Atlantic Canada and much of North America. They took to the skies in such unspeakable numbers that their migrations blocked out the sun. They accounted for more than a quarter of all birds in North America and were possibly the most numerous bird on Earth. A single flock observed in 1866 passing over southern Ontario contained an estimated 3.5 billion individuals. The flock was reportedly 1.5 kilometres wide, 500 kilometres long and took 14 hours to pass.

Like the great auk, the passenger pigeon was an important source of food for Atlantic Canadian communities before industrialization. This changed when Europeans declared war on this pigeon, capturing and killing them with great nets, shooting them, clubbing them, even obliterating scores of them with explosive powder and raiding their nesting grounds. Some accounts justified this slaughter by calling the passenger pigeon overpopulated. This is, of course, ridiculous.

The last wild Passenger Pigeon ever spotted was shot out of the sky over Penetanguishene, Ontario, in 1902. The last passenger pigeon on Earth, the last of the billions which once ruled our skies, died in captivity in September 1914, in the Cincinnati Zoological Gardens.

Unlike dates of historically significance, dates like 1812, 1918, 1945, 1969, our last encounters with these species are too easily forgotten, much like the animals themselves. We should endeavour to remember, for our sake if not for theirs.