On April 5, less than a week after the Labrador flag turned 40, The Independent received an email from Michael Martin, former New Labrador Party MHA for Labrador South and creator of the Labrador flag. Martin recently launched a campaign to educate people about the flag's true design, which has been manipulated to the point that many of the flags now flown across Labrador are misrepresentations. "The problem stems from efforts by unscrupulous dealers and manufacturers to get around the copyright requirements by creating flags that have the wrong dimensions, wrong colours and wrong shape and size of the black spruce twig,” Martin explained in the email. “The market is flooded with these 'bootleg' versions of the flag and it is a source of much concern to Labradorians who see these false representations as an affront to our heritage and culture.”

After receiving Martin’s email we decided to check the Labrador flag depicted on TheIndependent.ca's masthead. Of all the flag’s manufacturers, only Windco Enterprises in Portugal Cove on the Island got it right, he told us by phone on April 6 from his home in Corner Brook. The Labrador flag The Indy uses in its masthead is a digital illustration of a photo taken by John Martin in Labrador, who graciously allowed us to use his image. But through the photo imaging and editing process the original colours were lost, so Indy photographer and Landwash graphic designer Graham Kennedy is having a go at it to see if we can restore our Labrador flag to its original colours.

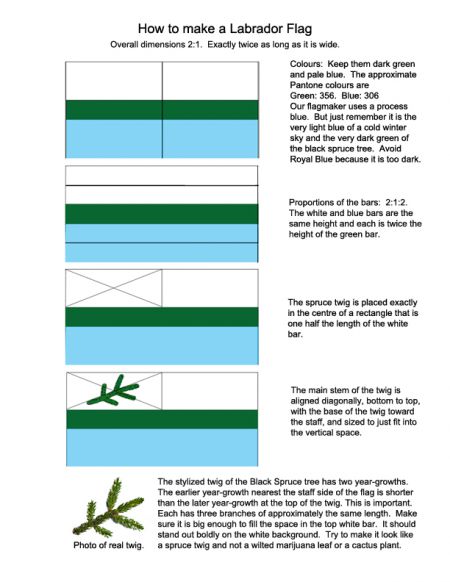

Things you should know about the flag

In 1973 the Newfoundland Government called upon the people of the province to begin planning ways to commemorate the 25th anniversary of Confederation the following year. In December ‘73 Martin—who had been elected to the House of Assembly as a member of the New Labrador Party for the district of Labrador South in a by-election in ‘72—and a few friends “decided that since the province was flying the colonialist flag of Britain we needed a flag of our own,” he recounted in 2002. “Since the government was not interested in creating a new provincial flag we thought it appropriate to make a flag for Labrador.

“Our intention was that this would be simply a celebration project and expected nothing further to come of it,” he continued in his 2002 letter. “We purchased some cloth in the appropriate colours. My wife sewed 64 flags — one for each town and village in Labrador, one to be presented to each of the three Members of the House of Assembly in formal ceremony, and two for ourselves. I took [a] felt marker and drew the twig on the white staff half of the flag.

“The flags were sent out to the communities with letters asking everyone to raise them on their flagpoles on March 31 to commemorate our becoming Canadians on April 1st, 1949. In a public ceremony in the main foyer of Confederation Building … the three flags were presented to the Labrador Members, myself included.”

The Labrador Heritage Museum, giving an account on its website of the significance of the flag’s colours, the white bar at the top of the flag “represents the snows, the one element which, more than any other, coloured our culture and dictated our life styles.” The blue bar at the bottom of the flag “represents the waters of our rivers, lakes and oceans. The waters, like the snows of winter, have been our highways and nurtured our fish and wildlife that was our sustenance and the basis of our economy.” And the narrower green bar in the centre “represents the land - the green and bountiful land, which is the connecting element that unites our three diverse cultures.

"The twig of the black spruce tree, in two year-growths, represents the past and the future. The shorter growth of the inner twigs represents the hard times of the past, while the longer outer twigs speak of our hopes for the future. The twig is typically in three branches and represents here the three original founding races of modern Labrador - the Innu, the Inuit and the white settler. The three branches emerging from a common stalk represents the commonality of all humankind regardless of race."

One purpose, a spectrum of colours

TheIndependent.ca columnist Brandon Pardy commemorated the flag in his Jan. 24, 2014 column “How Labrador got its colours”:

I don’t think anyone could have predicted how quickly and fervently it would be adopted … Within months the colours were flying everywhere. This was partly in response to political unrest, but in large part I think people believed in the idea of unity amongst the communities. It’s not an anti-newfoundland flag. It’s not a separatist flag. It’s a flag to celebrate the diverse identities of Labrador in a single image.

In the spring of ‘73 Martin gathered interested people together in Goose Bay to discuss forming a group to preserve Labrador’s heritage. The Labrador Heritage Society was then born.

“By this time images of the flag were being printed on souvenir items such as lapel pins, badges and car stickers,” Martin wrote in 2002. “Unfortunately the images did not conform to the original design. Invariably the colours were away off, usually with the green too light and the blue too dark. The horizontal bars became of equal width and the twigs in some instances looked more like leaves of the marijuana plant. It was an embarrassment.”

The Labrador Heritage Society applied for and was granted copyright of the flag’s design. “At the start the copyright was brought in to protect the integrity of the design, but we asked that people who were manufacturing the flag give the Labrador Heritage Society $10 or something like that to help them manage the business,” Martin told The Independent on April 6. “We thought this wasn’t a very big tax … Well, they figured if they changed the design they wouldn’t have to pay copyright, which is not true because if it’s sold under the name ‘Flag of Labrador’, then you have to have the correct dimensions and colours and all that. But the Heritage Society, not having any money, declined going after these people...so we just let it go. Now there’s hundreds of those damn things out there that don’t look at all like the Labrador flag … There are distributors in Labrador who are trying to find cheaper flags. It boils down exactly to economics. They want to get the cheapest flag available and they don’t care if it’s the wrong flag — they can sell it as the Flag of Labrador.”

Knowing many in Labrador “were born, lived and died under the flag,” Martin said he decided it was time to get a handle on the situation. “So the first thing we do is education...and we go out with this little style sheet and say, ‘If you’re going to make one’ down at your craft shop or down at the school art class or something, ‘here’s how to do it,’” he explained.

“We’re going to see how that takes off, and then there’s a thought that perhaps now we should be licensing one or two manufacturers only through the copyright holder, the Labrador Heritage Society, and then it becomes an offense if you’re manufacturing without a license … then we can go after you with a stronger case than just copyright. So that’s the next stage but we haven’t got there yet.”

A renewed call for unity against “exploitation”

Despite its original purpose, to serve as a “statement of identity — nothing more, nothing less,” the Labrador flag has been embraced by people and groups across the Big Land. The Nunatsiavut government used the flag’s colours in its own flag and the black spruce twig was used in the Franco-Terreneuvien flag. For some the flag has also become a symbol of Labrador independence and is currently embraced by individuals gathering to discuss and re-evaluate Labrador’s governance.

“Exploitation, it’s a part of our legacy, a part of our heritage, a part of our culture; we’ve always been exploited." - Michael Martin

“It was never meant to be a political symbol, and we made that clear right from the outset,” Martin said in the April 6 interview. “This is not a separatist movement, this is not a separatist flag. This is a flag that states who we are, what our culture is all about, what our land is all about and the connection of the people with the land … Down through the years some people have, in their protest movements, held up a flag. It’s their right to do so, it’s their flag, they can wave it wherever they please and for whatever reason. But the flag itself remains a statement of identity and it always will.”

There is one crucial point it seems Martin and those advocating for Labrador independence, or a dramatic restructuring of how The Big Land is governed, could agree on, however: the unfair exploitation of Labrador’s resources will not stop unless the people of Labrador do something about it.

“Exploitation, it’s a part of our legacy, a part of our heritage, a part of our culture; we’ve always been exploited,” he told The Independent. “I’ve got a document dated 1835. It’s a petition from the fishermen in Sandwich Bay to the Government of Newfoundland in St. John’s, and they’re saying that the impending fisheries regulations are going to decimate the salmon fishery and hurt the fishermen in the Bay. Nothing has changed. Sometime in the late 80s the Government of Newfoundland, and the Government of Canada I think specifically in this case — they changed the salmon regulations and they bought out all the salmon licenses and they deprived the salmon fishermen of their right to make a livelihood catching salmon.

“From 1835 to 1980 and on into the 21st century, this kind of exploitation continues, and it will continue because we’re a very small political entity,” he continued. “Votes matter. We don’t have enough votes to change things in the House of Assembly. We tried making a dent in it back in the 70s with the New Labrador Party. We made some changes because we had a sympathetic government in the form of Frank Moores’ Tories. Because they were sympathetic and saw the injustices being done, they corrected some things. But you’re not gonna correct them because of the overwhelming vote outside of Labrador for things that are important to other people for different reasons. And so, we’ll always be exploited.”

“So long as we are not unified, so long will the Government of Newfoundland and the Government of Canada exploit our resources." - Michael Martin

Martin said he’s happy to see a bit of resistance to some of the controversial resource development projects in Labrador: “In a democracy dissent is always healthy. People have not only the right but the responsibility to offer dissenting voices when they feel that something is wrong. That’s part of what democracy is all about and it’s healthy to do that, and I’m happy to see people in Labrador doing that.”

But he concluded with a sobering observation.

“So long as we are not unified, so long will the Government of Newfoundland and the Government of Canada exploit our resources. Why not? If they can take it without fear of any repercussions of course they’ll go ahead and take it,” he said. “So it’s important that people understand that they have to act in unison. I don’t think that’s going to happen to a great degree in Labrador because I’ve watched from early childhood, when I became aware of differences from within my own community, and then differences from within the district. Labradorians like to get at each other’s throats, and the ethnic [groups] are against one another, the various districts are against one another, the people in the community up on the point don’t like the people down on the bottom. It’s always been the same, and I would like to think at the beginning that the flag would have some effect on that—and it has to some degree—but I would like to see it a more unifying force. I would like to have people see it as a way of getting around their disagreements, and getting around their objections to one another for a common good. Because if they don’t stick together they’re going to continue to be exploited.”

This article was originally published April 16, 2014 in 'Landwash', a project of TheIndependent.ca.