Moira Peters and Sam Fraser were unemployed and struggling in the Halifax labour market when they discovered the Centre for Entrepreneurship Education and Development (CEED).

This Halifax-based, not-for-profit organization helps people start their own businesses by offering advice and financial support.

Peters is a wine enthusiast, who completed her sommelier training in New York State in 2007. The 32-year-old had been working in a restaurant on Long Island, an area gaining notoriety for its local wine industry, and had developed an interest in wine evaluation. “You’re using your body,” she says. “You’re using your senses to explore something in an intellectual way.”

Now she wants to share this experience with others. Upon returning to Nova Scotia, Peters hosted a few wine tasting parties for friends. One suggested she consider it as a business venture and the idea of a mobile wine bar was born.

Peters’ idea is to act as a hostess for wine-tasting parties to be held at the homes and offices of clients. She will lead guests through the ins and outs of wine tasting. There are different tasting packages to choose from, each consisting of around eight bottles of wine.

One package, The Neighbourhood, spotlights Nova Scotia wines. Peters hopes it will help promote the province’s burgeoning wine industry. For CEED, this contribution to the local economy is one of the most positive effects of entrepreneurship, and something Peters is almost as passionate about as wine.

But Peters got stuck trying to bring her idea to fruition. “In the back of my head this whole time I had this idea for a small business, but it was pretty daunting to think: How do I start a business? What’s the first step?” she says.

Sam Fraser found himself in a similar situation. The 32-year-old never planned on being an entrepreneur. He describes himself as a nerdy kid from New Glasgow who spent his high school years bent over board games.

Magic: The Gathering was the card game to play at the time, recounts Fraser, but the game’s marketing premise rubbed him the wrong way. As a collectable card game, players buy more cards to put themselves an advantage. “That offended me. I didn’t like that model at all,” says Fraser. He wondered how to create an alternative. “The obvious answer to that is let the players create the content,” he says.

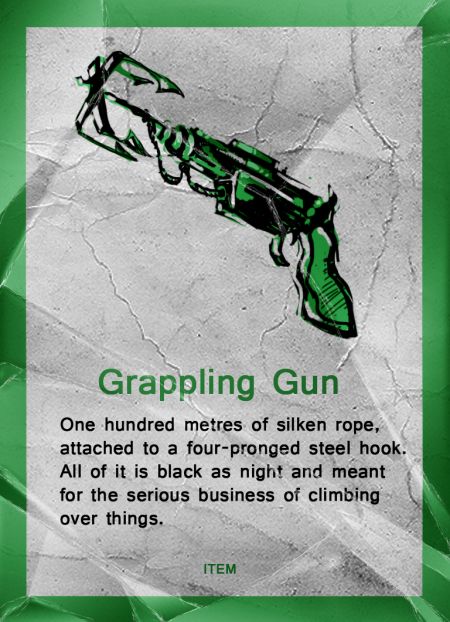

So Fraser created his own game, Thief, back in 2002. It’s a card-based game in which players use tools to break into buildings. The game comes with prefabricated wacky scenarios. Players are also given the opportunity to create their own.

But to get from pencilled sketches and misspelled instructions on cheap cardstock to glossy decks of cards was harder than he thought.

Then, Fraser heard about CEED. “I look it up and it’s almost too good to be true. I was really excited to find out about it,” he says.

Fraser and Peters both attended one of CEED’s monthly orientation sessions, last autumn.

By the new year, they were accepted into the Self-Employment Benefits Program. Its manager, Shawn Cunningham, says it has a continuous intake of participants of all ages hoping to start every kind of business imaginable, from elevator inspection, to massage therapy, to foot care.

Peters says the session impressed her with its demonstration of the services CEED offers and the commitment its managers have to the program. “It sounded more and more like a coherent, well thought out government program,” laughed this self-proclaimed critic.

Currently CEED has about 90 participants enrolled in the 40-week program. They are paid $350 per week in the first 25 weeks, then $300 per week thereafter. The program is funded primarily through Employment Nova Scotia, which also helps CEED offer low-interest rate loans to its clients.

The Self-Employment Benefits Program only accepts people who are currently (or have been in the last three years) on Employment Insurance (EI). In today’s labour climate, it’s one of the easiest criteria to meet.

Fraser was “downsized” from his job in October. Last autumn, Nova Scotia was recovering from its worst period of unemployment in more than two years, according to a Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey. In February 2011, Peters also joined that 9.8 per cent.

“I am a very employable person, especially in the hospitality industry. I have lots of experience in a wide variety of different hospitality contexts, and I have never had such a hard time getting a job,” says Peters, who describes how she “blanketed the town” with her resumes.

Peters was nearly done her 40-week allowable stint on EI when she discovered CEED.

She now has a restaurant job to help supplement her income, but she considers herself an entrepreneurial convert. She sees small business as the way of the future. Peters points to cuts in public service and government positions, corporative downsizing, and increased job specialization as hurting the labour market. “All of this is contributing to an economic environment where it's easier and perhaps more secure to make work for yourself than to depend on an employer,” she says.

After attending a CEED orientation session, participants have one week to draft a four- to five-page business concept outline. Once accepted into the program, “they’re matched with a business advisor that meets with them frequently, and they get to attend at least 20 workshops on all different topics of running a successful business,” says Cunningham. He adds that the program uses a series of mandatory milestones to keep its clients on track and to weed out those not willing to put an effort into their business plan.

Fraser praises the program’s “step-by-step process.” Currently, he and Peters are in the testing stages. In the past couple months, they’ve invited their friends and acquaintances to test out their business ideas first hand. By doing so, they hope to hone their plan and assess the viability of their businesses.

On Valentine’s Day eve, a group of late 20- and 30-somethings cluster in Moira Peters’ narrow galley kitchen. Squinting through wine glasses, they study the Nugan Third Generation Merlot within.

Next will come the Freixenet Cordon Negro Cava and the Gaspereau Tidal Bay. With each glass, Peters’ guests stumble through the elements of wine tasting: the eye, the nose and, of course, the mouth.

After several wine tasting parties and rave reviews from guests, Peters still feels unready to charge clients for her sommelier services. “I can’t help but have this massive self-doubt,” she says. “I mean it’s wine. People don’t need wine, you know?”

Cunningham says he has seen plenty of clients succeed with what he calls “destination” businesses, that is, those offering unique products or services to particular audiences. Halifax’s Two If By Sea Bakery & Café, Obladee Wine Bar, and The Loop Craft Café are examples of such CEED start-ups.

Along with these successes, 60 to 70 per cent of ventures begun thanks to the centre remain in business, estimates Cunningham. He describes Halifax’s current climate for business start-ups as positive, especially owing to low-interest rates on loans.

But CEED places most of the responsibility for success on the business owners. Cunningham notes the need for proper bookkeeping and financial discipline. Most importantly, he emphasizes the need for clients to have the confidence to make sales.

Fraser says he isn’t a self-promoter, and he considers himself to be working in a precarious industry: “Starting your own business as a game designer and publisher is not really recommended. Most people on the web forums who have tried it before say you invest a lot of money and a lot of time and at best you break even.”

So far, Fraser has invested just over $500 of his own money in his business idea. He has also applied for a $10,000 loan through CEED to produce his game. That is why he hosts weekly Thursday night play testing sessions. He needs feedback to create a sellable board game.

On Feb. 23, friends Steven Atkinson and Peter Shatford are hunched over a low, long coffee table in Fraser’s living room.

It’s Fraser’s turn. He reflects over the four tools at his disposal — cards with rudimentary drawings of pry bars, gas masks and impermeable boots — and the choice between two buildings to break into, with such safeguards as smoke alarms, security personnel and noise detectors.

Selecting another player’s building, he faces added security features, like impossibly high walls, dark pits of animals and three sword-wielding men. Fraser then devises a creative break-and-enter strategy using his tools.

It’s up to the other players to judge the feasibility of his plan — and of his game idea.

Fraser wants to have this initial print run ready for sometime in March. He is crossing his fingers people will dole out $30 to $40 dollars for a deck of 250 playing cards. He has included plans to create expansion packs for Thief. It’s a card game moneymaking scheme similar to those he deplores but which he is willing to try due to pressure from CEED to make a profit.

“The program is designed to help people make money, completely irrespective of their business idea,” says Fraser. “What's wrong with this approach? Only the things that are wrong with the capitalism system in general. Personally, my priority is to make innovative games first and contribute to the dialogue of game design, and make money second.”

CEED expects Fraser and Peters to be making sales by mid-May. The centre does not take a cut of its clients’ earnings, and it will be more or less out of the picture after their 40-week stretch comes to an end in October.

Despite this, Fraser is already able to see the program’s lasting impact: “I don't feel like I'm delaying something anymore. When I was working at any other job, I felt I was doing this temporarily and that I was actually going to be doing what I really wanted to be doing in the future, even though I didn't really know what that was,” he says. “Finally, I feel the work that I'm doing is actually contributing directly to my sense of self.”