SOMEWHERE IN NEW BRUNSWICK...

Six am.

In the darkness, I feel the wind biting at the back of my neck. The leaves under my feet crunch like a multi-colored carpet of eggshells.

“Frost last night,” John tells me, “good thing I got the last of ‘em covered.”

We continue trudging through the forest. Every so often we stop. John listens intently in the pre dawn light. It’s not the wildlife he’s worried about, he’s nervous about law enforcement. “Usually when they find a stand of pot, they just pull it out and leave with it,” he whispers, “but if I was to run into them where my plants are, how am I going to explain that? Wouldn’t be good.”

I nod in agreement.

In Canada, the charges for cultivating 50 marijuana plants could range from a small fine, to up to several years in prison, depending on the jurisdiction and the judge. After a few moments, we’re on our way again. I can’t help but feel nervous. Each shadow by every tree could potentially be law enforcement. John isn’t carrying a gun, which makes me feel a little better. The results of a confrontation with an armed pot grower could be disastrous.

The sun breaks through the trees and I see it a lumpy landscape in front of me. In a clearing that is dotted with small trees and ferns, several large marijuana plants, almost six feet tall, are covered with bed sheets to keep the buds from freezing. We remove the covers from the foliage. The material is damp and frosty, but underneath the plants seem to be fine.

John knows what he is doing.

John is a criminal, according to Canadian law. And if the estimates are right, there are hundreds, if not thousands of more criminals like him in Atlantic Canada. Average, everyday, citizens who’ve started cultivating pot to increase their bottom line. John is a seasonal worker, he’s married and has a couple of kids. “There’s never enough money to go around,” he explains. “It’s not like I’m making heroin. Everybody does it.”

Not everybody does it, but many people do. And it has become socially acceptable in most places. Even if you do not indulge in weed, most certainly you are related to, or know someone who does. Whether you are for it, or against it, you have to admit, it’s everywhere.

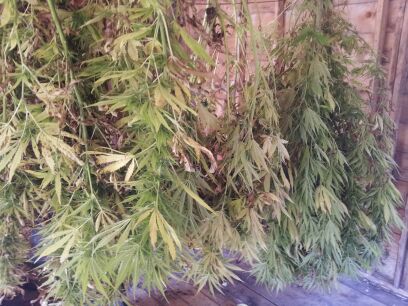

We leave the plants and make our way down a path to a small shed, constructed of lumber and tin. Inside, plants are hanging upside down from the ceiling, their roots cut away. This speeds the drying process. There are small slots, each about the size of a cigarette pack, in the walls to let air pass through, ventilating and keeping moisture at bay. “There can’t be any dampness in the buds once they are stored,” he says as he notices me eyeballing the room, “or mold will set in. Then they’re worthless.”

A kitchen table for four and several chairs are in the corner. Sitting on the table, is a curious looking item that I’ve never seen before. John explains that it’s a “bud bowl”.

It is a contraption with an electric motor and rubber beaters that separate the marijuana buds from the leaves. The device is actually two large, stainless steel, bowls that fit together. The bottom bowl has a screen that the buds sit on. The top has the motor and rubber beaters. When the device is turned on, the beaters “beat” the leaves off of the buds. The leaves fall through the screen into the bottom of the bowl, and the buds emerge ready for drying. Although there is no electricity here, John has power thanks to a car battery, an inverter and a solar panel to keep it all charged up. “Don’t need no noisy generator to attract attention,” he explains.

The ‘bud bowl’ saves him hours and hours of work. The buds used to be clipped by hand using scissors. A tedious job at best. Now, he just plucks the buds from the branches, tosses them into the bowl and in less than a minute they are clipped. “I got the unit for about $600, and it paid for itself the first year in time saved.” he says with a chuckle.

Once the buds are clipped, John places them on sheets of newspaper, spreading them thin enough so air can penetrate them and finish the drying process. After a four of five days, depending on the humidity, they’re ready to be bagged and frozen.

Naturally, I am curious about a few things. For starters, where does he get his seeds?

Turns out, there is a person that raises seedlings and clones them. (Clones are made by removing leaves from a mature plant, and placing them in water. Roots will form and they become plants, clones of the mature one.)

“It’s a lot easier for me, and more discreet,” John says, “I don’t have to fill all my window sills with plant boxes in the dead of winter. And my guy raises the type of plants that I want.”

So what type does he want? Or does the public want. There are hundreds of varieties out there, all “promising” their own distinct type of high.

One strain of bud that has really caught on is Kush, which is a bud that gives the user a particularly intense high, affecting both the mind and body. “Kush is really popular, but it’s hard to grow. It seems to prefer the warmer climates. I have the best luck with a strain of marijuana called purple haze. The yield is pretty decent, and it’s no problem to get them matured before the cold weather hits.” Users claim purple haze gives them a quick and long-lasting head rush.

Now, of course, the big question is the money. And about how many buds each plant yields on average. “You know, people always think you can get a pound of buds per plant,” he says, “it’s possible in a southern state with a warm climate, but not in the Maritimes. At least, I can’t get that much. The season is just too short. Every year I grow about 50 plants, and I wind up with about seven or eight pounds of buds to sell. If I was to sell them right after harvesting, they’d be worth about a thousand dollars a pound. I try to wait and sell them later on when the market is better. Most years I can get around fifteen hundred, it works out to between 10 and 12 thousand a year. I could get a lot more if I wanted to sell it by the ounce, but that attracts too much attention. I sell it all to one guy, and whatever he does with it is his business.”

John can only assume the drugs will wind up in the hands of street dealers. It’s like that when you sell anything, for that matter. Once it leaves your hands, there’s no control of what happens to it. However, organized crime wouldn’t have any use for marijuana if it was legal for everyone to buy and sell.

I ask him if he feels bad about making tax-free cash money. And how does he handle having that much cash around.

He laughs.

“Spending it is no problem. I have kids, bills that keep piling up. It’s gone in no time. I pay income tax when I work, when I draw EI, then when it’s time to do my income tax, I have to pay again. My wife has been waiting for six month to have a surgery, and the government keeps raising the taxes on my land. Do they feel sorry for me?”

It’s hard to disagree with him, especially when you look at the bigger picture. Provincial governments in the Maritimes are strapped for cash. In New Brunswick alone, the deficit is approaching 600 million dollars. Waiting times for hospital services in all four Atlantic Canadian provinces can be long. As inflation causes property values to rise, our property tax bills increase, even though our income does not.

Would legalizing marijuana create a flood of tax revenue? Or would it create a host of other problems? Even John doesn’t know the answer.

“Legalizing it would save the federal government a bundle, because they spend millions every year searching for plants, and even they admit, they don’t get 10% of them. It’s a waste of money. But if they legalized it, what would happen to people like me who grow it? Would we be in the cross hairs like cigarette smugglers? And where would people be allowed to smoke it? You can’t smoke cigarettes anywhere now, wouldn’t pot be the same?”

He’s right. Legalization raises more questions than answers.

Economists estimate that the fight against marijuana is costing the Canadian government between one and two billion dollars per year. One thing is for certain, until governments address it, people like John will take huge risks to continue growing it, and reap the benefits. It’s an issue that is not going to go away anytime soon, and will no doubt keep unfolding in our Maritime forests.

![John's crop of Purple Haze is ready for harvest. [All photos: J. Lawson] John's crop of Purple Haze is ready for harvest. [All photos: J. Lawson]](../../../sites/mediacoop.ca/files2/mc/imagecache/page450/bud_6.jpg)