Disclaimer: Some scenes in this story may be triggering for people who have experienced sexual assault. If you need support, call the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre at 422-4240 from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. to make an appointment. The after hours phone line is 425-0122, but it is only for sexual assaults that have happened within the last 72 hours. Names in this story have been changed to protect the identities of sexual assault survivors.

The first day of grade 12 was over so Jason and his two buddies picked up a couple eight packs from the cold beer store in his Nova Scotian hometown and drank them behind the hockey rink. Jason had more than usual, averaging between a pint and a quart of hard liquor a day since junior high. When they left for a friend’s house, he trailed behind the guys. A Kids Help Phone poster grabbed his attention. Lately he had thought about calling the hotline. He took out his phone and dialed the 1-800 number.

“I need help,” he said when the woman answered. He began to sob and couldn’t stop. She asked if he was in danger. He said no; it had happened 10 years ago.

His friends saw his tears and asked what was wrong. They pushed him until he told his story out loud for the first time.

When Jason was eight, his parents paid a babysitter to take care of him over a period of a year and a half. The touching started with innocent games of tag, which turned into wrestling and eventually into groping, each time with less and less clothing, “encroaching on boundaries until they started to disappear.”

The babysitter – an older boy in high school – said no one would believe Jason if he told, and that his parents would be mad at him, so he stayed quiet.

“I shut down. I was like a shell and I kind of hung out inside that shell. I stopped using ‘feeling’ words. Anytime someone asked me what was going on I said ‘regular’ or ‘neutral’ or ‘average’. I stopped being expressive at all.”

His parents took him to a therapist. There was a book in the therapist’s office about a kid who had a secret but couldn’t tell anyone.

“I was screaming inside myself that I recognized exactly what that was about.” But he couldn’t say it out loud.

When he was 13, Jason began drinking to deal with his trauma, which manifested in night terrors. Nearly every night for five years he was scared to fall asleep. Sometimes he woke up paralyzed, able to open his eyes but unable to move his body. Other times, as he drifted off, he hallucinated scenes of torture and death. Often he couldn’t wake up from vivid nightmares. To cope, he began taking shots of vodka each night before bed. Jason coaxed cab drivers to buy him liquor with the money he saved from his paper routes and computer cleaning business.

His problem peaked in his 20s when he downed a bottle of pills with a quart of vodka and called in sick to work. He vaguely remembers the police in his apartment. He woke up in the hospital.

“I’m by no means past it, but it’s two years since it’s controlled everything I do. It was live or die because I ended up in the hospital trying not to live anymore. It was either get on with living, or choose the other…” he says, trailing off.

Jason, now 26, has been sober for two years.

One in six boys and one in four girls are sexually assaulted before the age of 16 according to Statistics Canada.

Though males make up the smaller side of rape statistics for any demographic, Jackie Stevens of the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre says the root cause is still the power dynamic of one person exerting control over another.

“Predominantly males who are sexually abused are sexually abused by other males, and statistically people who are committing sexual violence mostly are men,” she says.

“Particularly if it’s a male assaulting another male, that is the ultimate way – how do you control another man? By reducing him to the equivalent of a woman, who is not your equal. How do you do that? Through sexual domination. The flip side, for women who are sexually abusing, they don’t have power or control, so how do you get power and control? By violently dominating someone else. I would see sexual violence as a tool for that power control.”

Anyone can be sexually assaulted and anyone can sexually assault, Stevens says. The epidemic surpasses all societal barriers. However, layers of oppression contribute to the initial problem, and make it harder for vulnerable people to get help.

Believe survivors

When Jason told his mom he was sexually abused, she said it didn’t happen, that he made it up.

“As a symptom, you learn to manipulate and that involves a lot of lies and storytelling and that kind of stuff, which I used to do habitually,” Jason said. “So she wasn’t willing to go down that road at all.”

“That’s one of the most common things that we hear from people,” Stevens says. “That they’re not believed, or that they’re afraid they’re not going to be believed, or they’re going to be blamed in some way for it.”

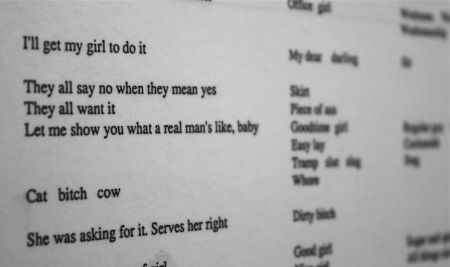

She says because our society still subscribes to myths and stereotypes surrounding who gets sexually assaulted and why, it is easier for us to doubt a person who says they were raped. If someone has previously lied to their parents or friends, or if they are mentally ill, we are sometimes quicker to blame or disbelieve that person than to immediately accept that they were raped.

Jason stayed quiet for 10 years because society perceives sexual assault as “something different, and by calling attention to that, it makes you different.”

Even today, he doesn’t talk openly about it.

“You don’t want that to be the only label you have. … By broadcasting that you just get terrified that it’s all people are going to see.”

At the time, Jason partially blamed himself. His babysitter told him he had wanted, and started, the abuse.

“Initially you get terrified that it was you who did something wrong, it was you who was in trouble, it was you who would be punished. There’s a panic that you’re not in control of your own body anyway. So losing that control to someone else gives you such a fear that it makes irrational thoughts rational. Terror supercedes what your rational course of actions would be.”

“For a lot of people there’s still that shame and fear attached to being sexually violated that would certainly keep them from wanting to come forward because they’re not sure how people will perceive them,” Stevens says.

The Avalon Centre says believing and supporting a friend or family member who tells you they were sexually abused are the most important things you can do.

A step-by-step guide on the centre’s website, avaloncentre.ca, advises the following actions if someone tells you he or she has been sexually abused.

1. Believe her (or him) without condition

2. Speak to her (or him) without blame or judgment

3. Do not judge her (or his) response to the assault

4. Allow her (or him) to make the decision of what happens next

5. Take care of yourself

The full guide can be found here: http://www.avaloncentre.ca/supportingawomaninyourlife.htm.

This is the final part of a three-part series. Read part one here and part two here.

Stay tuned for an update later today: possible solutions for sexual assault according to El Jones, Jaclyn Friedman and the provincial government.