Disclaimer: Some scenes in this story may be triggering for people who have experienced sexual assault. If you need support, call the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre at 422-4240 from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. to make an appointment. The after hours phone line is 425-0122, but it is only for sexual assaults that have happened within the last 72 hours. Names in this story have been changed to protect the identities of sexual assault survivors.

Jenna never wants to see her purple semi-formal dress again. She loves it, but it reminds her of that night at the beginning of April when someone slipped what she suspects was Ketamine into her drink.

When she finished class at 4 p.m. that day, Jenna rushed to her friend’s place to get ready. She wore her mom’s sparkly earrings and bracelet, black kitten heels and the silky, knee-length dress. It was the end of the year celebration she’d been waiting for – a chance to blow off some steam with her friends and classmates at Dalhousie.

She remembers everything about that night – feeling happy, dancing to bad music with her friends at the Palace – up to a point. It’s as if the rest of the evening didn’t happen. She woke up in her bed feeling nauseous and hung over. She stepped into the shower and felt bruises on her chest. It took her the rest of the day to piece together what happened. When she did, she felt embarrassed. She recalled blurry flashbacks of a man in her room, on the third floor of her house. He was white, but she doesn’t remember anything else about him, only that he sat there in her computer chair, looking at her from across the room. Jenna asked him to leave, but he wouldn’t.

At the hospital, nurses confirmed her suspicions with a rape kit. They gave her a list of side effects associated with Ketamine, a “date rape” drug. Her symptoms fit perfectly. The police took her pretty purple dress for DNA evidence.

We tell women to cover their drinks, dress conservatively, and walk home in groups – never alone at night. While Jenna still thinks those are great ideas, she says they didn’t work for her. She covered her drink as often as she could that night, and she stuck with her friends. Jenna worries no one is looking at the big picture. It’s not her fault she was raped; she doesn’t take responsibility. Instead, she blames the man who raped her. Too often the media, the police, our parents, our friends are quicker to point out flaws in sexual assault survivors’ actions.

‘Don’t get raped’

Section 271(1) of the Criminal Code of Canada defines “simple sexual assault” as: “Any attack of a sexual nature in which force is used. No physical injury is necessary to prove that an offence has occurred.” When prosecuted as an indictable offence, this form of sexual assault carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison.

Nova Scotia has the highest rate of sexual assaults in the country – double the national average, according to a 2009 report by the Nova Scotia Advisory Council on the Status of Women. A 2006 Halifax Regional Police report shows that on average one sexual offence is reported per day in Halifax. However, a 2005 Juristat report showed only eight per cent of sexual assaults are reported in Nova Scotia.

This year the Avalon Sexual Assault Centre, located on Dresden Row in Halifax, declared May Sexual Assault Awareness Month. On Thursday, May 20, at Province House, politicians and community members plan to speak out publicly against sexual assault.

The centre defines sexual assault as: “Any form of sexual activity that has been forced by one person upon another. Without consent, it is sexual assault. Sexual assault can happen between people of the same or opposite sex. It includes any unwanted act of a sexual nature such as kissing, fondling, oral sex, intercourse or other forms of penetration, either vaginal or anal.”

Avalon’s mission is to shift responsibility from the survivor to the attacker by educating the public.

Before we begin our interview, Jackie Stevens closes her door, as she usually does when someone comes into her office. When a woman, or sometimes a man, sits in the comfy chair beside her desk, the Avalon co-ordinator of community education wearing electric blue cat-eye glasses doesn’t judge or offer advice. Instead she gives the person plenty of information so he or she can make an educated decision.

Too often the people who sit in that chair blame themselves.

“If I hadn’t trusted that person, if I hadn’t gone out drinking with my friends, this wouldn’t have happened to me,” the sexual assault survivors tell Stevens.

Rather than automatically thinking that way, she says society needs to see that an attacker has chosen to take advantage of someone who is vulnerable.

When she reads articles about drunk driving, the police are quoted telling people to stop drinking and driving. But when she reads articles about sexual assault, there is no warning telling would-be attackers not to rape. Instead, the authorities tell potential victims to take precautions.

She doesn’t claim to see every article, but yellowing copies of the Chronicle Herald are piled alongside today’s issue in a bin behind her.

In a Metro News article from March 19, Dalhousie University spokesperson Billy Comeau told students to “be aware of their surroundings and to take all precautions when they are out travelling” in response to a man grabbing a 19-year-old female student from behind in Halifax’s South End. In a Chronicle Herald article from May 14, a prosecutor told parents to “watch what their children are doing, both online and within the proximity of their house and outside the house,” in response to a Halifax woman allegedly luring a girl over the Internet and sexually assaulting her.

“Rather than always putting out the messages of ‘don’t walk alone’ or ‘don’t drink’ or ‘don’t talk to strangers’ – all of those things – we need to say ‘don’t sexually assault,’” Stevens says.

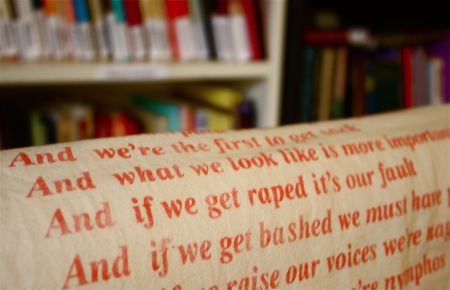

As a result of these misplaced messages, we say ‘she shouldn’t have been walking home alone late at night’ or ‘she shouldn’t have worn a short skirt’ rather than ‘he shouldn’t have raped her.’

We think ‘don’t get raped’ rather than ‘don’t rape.’

The way a woman dresses or acts does not cause or prevent sexual assault; an attacker rapes someone because they want to exert power and control over him or her. The attacker is solely responsible for the crime. However, this responsibility is lost in translation through the police, the courts, and the media.

Eighty-four per cent of people over the age of 15 who are sexually assaulted are women, according to the 2009 status of women report. More than 90 per cent of those accused are men.

Sexual assault is a social problem, Stevens says, with lingering patriarchal structures* at the root of offenses by men toward women.

“There’s a lot of perception of sexual assault as an isolated incident that happens to certain people and it’s perceived as a very individual issue. The Avalon Centre takes the approach that sexual assault is a social issue and that the root causes are based in patriarchy, violence, oppression and inequality. Sexual violence is just one form of how that inequality and power imbalance is played out.”

Stevens says sexual assault and violence against women is interconnected with sexism and other forms of oppression such as racism, homophobia, and discrimination based on disability, gender identity, cultural background and lifestyle choices.

“Often times people who do experience sexual violence may be targeted for very specific reasons because of their vulnerability,” she says.

Jane Doe*, a local activist who also works at the Dalhousie Women’s Centre, wouldn’t be considered pushy if she were a man. Her voice is louder than the average woman’s. Her tone is aggressive.

“If I’m too confident, I’m a bitch,” she says.

Doe agrees that the root causes of male to female sexual assault are male privilege and power imbalance.

“Women weren’t legally human beings until 1920. If you’re property up until 1920, what role did sexual assault play in the world? Zero. There’s no such thing as rape – only for women. The pressure was on women to not allow men to ‘ruin’ them because women’s value and worth was placed in their virginity, their purity, so they could sell their sexuality to a man as property.”

As a result of historical imbalances, she says young men often feel entitled to “get drunk and get laid,” especially in a university atmosphere.

One in five male university students surveyed in a 2006 StatsCan study said forced intercourse was alright “if he spends money on her”, “if he’s stoned or drunk”, or “if they have been dating for a long time”.

One in five Canadian women surveyed in a Juristat report said they had unwanted sex with a man because they were overwhelmed by the man’s continued arguments and pressure.

“If we can change the response and how we think about sexual assault then we will change the rates of sexual assaults because it becomes less natural, less normalized, there’s more public scrutiny and judgment around it,” Doe says. “The problem is it’s very much a part of male culture.”

This story is part one of a three-part series. Read part two here, and part three here.

*Name has been changed.

*According to Avalon, “patriarchy” refers to “the current societal framework, the structure of which has historically kept men in positions of power and authority in society, and has encouraged the domination of other nations, races and cultures of people for economic and political gain.” In the not-so-distant past, women were placed in inferior roles and their sexual, financial and personal autonomy were suppressed. That framework still lingers today; women are still not equal to men.