Halifax Media Co-op

News from Nova Scotia's Grassroots

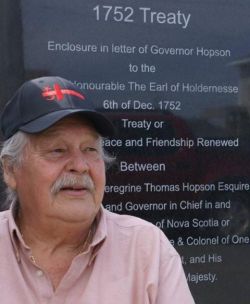

In Memoriam – Reginald Maloney

June 6, 1941 – December 3, 2013

A Reflection by Tony Seed*

On Tuesday, December 3, 2013, Keptin Saqamow Reginald Maloney, 72, left us forever when he passed away in Colchester East Hants Health Centre in Truro, Nova Scotia, surrounded by family and close friends.

A respected Elder, a political leader, Chief, a proud Mi’kmaq warrior and a friend, Chief Maloney was a leader of the epochal battle of the Mi’kmaq nation in defence of their hereditary rights and to affirm their right-to-be.

With the Union of Nova Scotia Indians, he led his community to take the first ever Treaty case to the Supreme Court of Canada and won. The R. V. Simon (1985) case declared that the Mikmaq Treaties signed with the British colonialists in the mid-1700s are as valid today as on the day they were signed.

The decision overruled the contemptible and racist R. v. Syliboy (1929), which had held that the Mi’kmaq Nation lacked “the capacity to enter into an enforceable treaty” as the Treaty of 1752 “was a mere agreement with a handful of Indians”and thus the Numbered Treaties were to all extent and purposes void. Syliboy gave free rein to the provincial government to use reactionary rules and regulations to suppress traditional Native hunting and fishing in violation of Treaties with the British Crown, and open up so-called Crown land to monopoly exploitation, especially the growing, mainly U.S. pulp and paper and hydro-electric interests.

Despite this legal victory, successive Nova Scotia governments attempted to subject the Mi’kmaq to further restrictions with game and other laws under the Lands and Forests Act. Chief Maloney again came to the fore to champion the struggle of the Mi’kmaq in the 1990s for their rights; a tumultuous movement to assert native logging rights developed in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick and “an unfamiliar season of hope” for communites plagued by impoverishment. Scores of Mi’kmaw and Maliseet were arbitrarily arrested and prosecuted for logging on so-called Crown land, while the private right of Stora, Scott Paper, Irving and their ilk was entrenched, codified and granted impunity.

In the wake of the 1999 Marshall Decision of the Supreme Court of Canada, Reg Maloney led Indian Brook Sipekne’katik First Nation for several years in a momentous struggle in defiance of the federal Department of Fisheries, RCMP and CSIS, big media, and the colonial divide-and-rule tactics in the service of the fisheries cartel.

The steadfast resistance of the Mi’kmaq of Indian Brook and Burnt Church Esgenoôpetitj First Nation in New Brunswick in parallel with the resistance of the small and traditional inshore fishermen stayed the hand of this dastardly alliance and its black aim of turning fisher against fisher, Native vs the small inshore fishermen, and of creating a race war throughout Maritimes Canada.

This experience of unity in action to affirm the right to be led to his participation in the Halifax International Symposium on the Media and Disinformation. Chief Maloney opened it on June 30, 2004 by delivering the fraternal welcome of his people to the participants from North America, Europe and Asia. “The greatest disinformation we have faced is that of the ‘discovery doctrine’ of the Spanish, Portuguese and British colonial powers, which still ravages us today,” he pointed out in his welcoming address.

His daughter, film-maker and photographer April Maloney, premiered her evocative documentary Treaty Tribulations: The Indian Brook Fishing Dispute at the Symposium. He remained true to his principles and, to the end of his days, he continued to sympathize with all those stood for their rights. In 2010 he was invited honourary chair of Halifax May Day, International Working Class Day, only to be called away by a family responsibility.

Reg Maloney served as Chief for two decades of Indian Brook Mi’kmaq First Nation up until 2004. He also spent four years on band council after that, was an Atlantic Chief representative on the AFN National Fisheries Committee and served (Keptin Saqamow) on the Mi’kmaq Grand Council.

Reg was a man of word and deed, whose word was his deed. We collaborated on a number of initiatives since 2004 and his “retirement” in the context of the program of Shunpiking Magazine and its Mi’kmaq / First Nations supplement, People of the Dawn.

He strongly encouraged our initiative to provide enlightened information on the real life of the Mi’kmaq – a definite people and land, with a past and a future, a language and a culture – and to create public opinion amongst Nova Scotians for necessary change. This was to the extent that he generously offered to get financing from the AFN Atlantic council for People of the Dawn, which he viewed as a collective work.

On another memorable evening, we sat together and participated in a long distance educational video broadcast from the Shunpiking offices with students in a course on globalization at the University of Lethbridge, elaborating the forces in combat in the Maritimes fisheries in defence of livelihood and rights.

The discussion with the Albertan students and their professor, Tony Hall, was lively and animated. At one point I read a quote from Fred Sears, a inshore handline fisherman from Cape Sable Island and well-known activist with the South West Nova Fishermen’s Rights Association, that I had featured in an article I had written on the struggle around the Marshall Decision at that time: “I am for the Natives. I am for their right to participate in our fishery, and to invest and build their resources and expand the fishery by squeezing out the corporations,” Fred had told me that on October 14, 1999, during a recess in the trial of fourteen handliners arrested by the DFO for exercising their traditional rights in a protest fishery in August, 1997. Sears’ sentiments were echoed by others attending court that wet and windswept day in Barrington Passage, views one never read about in the racist media.

Although the dynamics had changed somewhat since 1999, Reg immediately interjected, “how do we meet these men!” He later recalled a speech by the late Donald Marshall on a similar theme, calling on the Mi’kmaq to develop their own self-reliant producer co-operatives and limit the power of the fisheries cartel. People fighting against a common enemy, no matter the distance between them, eventually gravitate to one another, come what may.

Our last rendezvous though brief was on one beautiful summer day in 2010 when for the first time I visited Indian Brook and shubiefm radio at his and April’s kind invitation. He had asked sometime before if I had ever visited; when I replied, “No, unfortunately, I never have been invited,” he laughed with that broad smile of his, saying “Tony, you are the first White man I have ever heard say that he needed an invitation (to enter Mi’kmaq country).”

He was a quiet and gracious, modest and humble, respectful and down-to-earth man.

I deeply mourn his loss.

I send my deepest condolences to his devoted wife and partner Tanya Maloney, who was with him to the very end; his daughters, Mary Elizabeth Brooks, Amy Maloney-Ward (Roger), April Maloney, Cheryl Maloney, Lori Ann Maloney, Julie Maloney, Tasha Syliboy, Angel Paul (Jesus Flores), Velvet Paul, Melanie Paul, Autumn Dawn Maloney and sons, Leander (Lefty) Paul, Leo Paul, Jerome Paul and Drew Maloney; all his grandchildren, great-grandchildren and godchildren – and to the Mi’kmaq Nation and the Mi’kmaq Grand Council.

The funeral mass was held at St. Kateri Catholic Church in Indian Brook on Saturday at 2 p.m. Internment followed in St. Catherine’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, Indian Brook.

*Tony Seed is a contributing writer, publisher and longtime political activist. This reflection first appeared on Tony’s blog at http://tonyseed.wordpress.com

The site for the Halifax local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.