Halifax Media Co-op

News from Nova Scotia's Grassroots

Why Some of Us Aren’t Thrilled About IKEA’s Return to Halifax

The news that IKEA is making a glorious return to Halifax this year has been met with a jubilant chorus of rejoicing. But there are some reasons we should be skeptical of the gentle blue giant.

Sustaining what, exactly?

There is a lot to admire about IKEA and its seemingly earnest commitments to ecological sustainability. More than almost any other huge global corporation IKEA challenges itself to constantly improve its ecological performance, seeking to power its stores on renewables, practicing impressive recycling programs, using the latest, most cutting edge manufacturing and transportation techniques and more. They also claim, probably somewhat accurately, that the design of many of their household products like lighting fixtures and faucets reduce waste and energy consumption in the homes of consumers.

At an IKEA production facility in Sweden

But it’s all too easy to focus on these beautiful details while ignoring the bigger picture. IKEA’s business-model is the mass production of cheap, disposable furniture and household goods. While the design of IKEA items is sometimes impressive (or at least whimsical), the reality is that most of its furniture is made out of cheap materials and destined to break and be replaced within a decade. IKEA, which represents about 1% of the world’s annual use of forest products, boasts that 23% of their wood meets Forest Stewardship Council standards (and there have been sound critiques of how these standards are determined and enforced), but that means 77% do not.

Further, let’s not deceive ourselves: the design and layout of the stores is carefully crafted to encourage us to buy as much as we can, not as much as we need. This is absolutely essential to IKEA’s business-model. Needless consumerism is ecologically unsustainable, no matter how green the production of goods or the store environment may be.

IKEA is not a Swedish company. It is a global company, mostly owned by Swedes. It sources finished products from over 1,000 suppliers in over 50 countries. Many products are manufactured in China (20%), Poland (18%) and other low-wage countries, and often made out of materials sourced from the far-flung reaches of the world. Bringing all these pieces together and then shipping the final products to IKEA stores in places like Halifax is ecologically devastating — the company reports that it alone logs over 1.5-million shipments annually, and that does not include the transportation of many raw materials earlier in the supply chain.

No matter how green the process, hyper-consumerism based on globalized manufacturing is fundamentally ecologically unsustainable.

A humane workplace?

IKEA’s arrival in Halifax promises jobs, which, in a province and city with high unemployment, is appealing. But what sort of jobs? Perhaps because of its socialistic Scandinavian roots, IKEA is a bit kinder than its retail competitors in terms of wages and working conditions. For instance, IKEA prides itself on a relatively generous parental leave policy and an enthusiasm for hiring people with disabilities. They also boast a generally positive and relaxed work environment and training and development for workers who want to move up or around in the organization. These are good things, surely. Yet the reality is that most of the jobs at IKEA are part-time, low-skill, low-paid and “precarious.” Yes, IKEA’s part-time, low-skill, low-paid and “precarious” jobs are a bit better than Walmart’s. But that doesn’t mean they’re actually objectively “good” by any reasonable humane standard.

Further, IKEA has a dubious history with unions. For instance, in May 2013an IKEA store in Richmond BC locked out its workers precipitating a horrifically drawn-out 17-month long strike over wages and working conditions. Especially at issue was scheduling and hours for part time staff, where IKEA wanted to retain maximum “flexibility” and workers wanted some modicum of income security.

As indicated above, while IKEA may provide slightly better working conditions, benefits and compensation than its competitors, it is a company that is still fundamentally based on the exploitation of workers around the world, by the subcontractors who source the raw materials (word, plastics, metals, etc.) and who manufacture the materials into furniture and household goods.

And a final word on this topic: The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the United Way have calculated that an hourly “living wage” in Nova Scotia is $20.10. If IKEA pays any of its workers less than this wage (and across the country it tends to pay most employees only slightly more than minimum wage), it is exploiting people. It’s legal, it’s typical of the retail sector, but it’s bad for humans and unethical for a corporation that made over $5-billion CAD in profit in 2014.

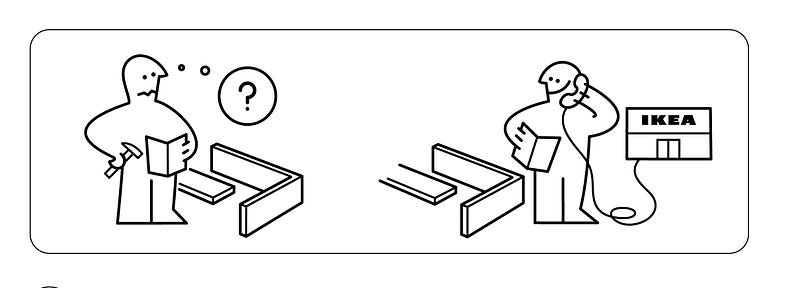

Assemble yourself (or else)

It’s not only employees themselves who are exploited. IKEA has built its brand and made a fortune on creating furniture that comes in slim, stackable boxes (allegedly for ecological reasons — they’re more efficient to ship that way). But from one perspective what’s actually happening here is the outsourcing of construction labour to the consumer. Now obviously this is no chain gang, it’s actually kind of fun (until you lose one of the little metal pieces and you’re left with a dangerously incomplete tower of pressboard looming over your living room). But it is part of a broader trend to offload work onto consumers. Think of automatic check-out machines in grocery stores (or, indeed, at IKEA), or of the “sharing economy” where services like AirBNB transform consumers into producers of value. Social media corporations are another good example: Facebook users do the “work” of generating the data, connections and desirability of the social media ecosystem. The company just maintains a minimal digital infrastructure and harvests the massive profits from advertising, metadata sales and, importantly, financial speculation.

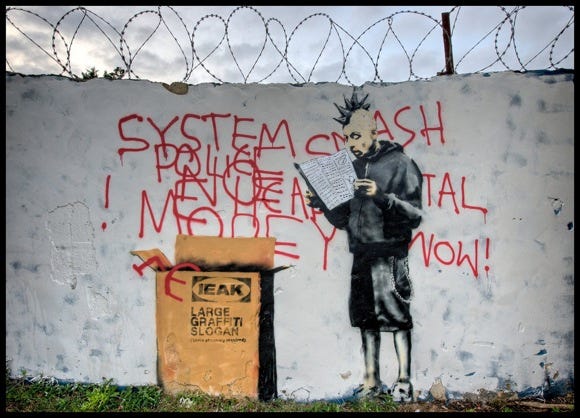

Banksy’s take on IKEA and resistance to it

This argument may seem far-fetched, but it is part of a by-nowwell recognized economic and sociological trend: in spite of our society being richer and more technologically advanced than ever, people are working longer, harder and for less. In fact, in an age when employers routinely observe their workers on social media and when everything from one’s volunteer activity to one’s Fitbit data can have an influence on one’s chances of career success, work has begun to bleed into everyday life in disturbing ways. That’s not all IKEA’s fault, but it does contextualize their approach and their success.

Essentially, ours is an age where we have each had to imagine ourselves as an “entrepreneur,” constructing a personal “brand” and hawking that product in a cutthroat and competitive labour market. In a moment when the Governor of the Bank of Canada can, without blushing, tell young Canadian workers they should expect to change careers 5–6 times in their lives and that they should work for free to gain job experience during economic downturns, we can begin to sense the scope of the problem. We have set ourselves up for a life of constant movement, mobility and uncertainty.

And in a way, this is what has led to IKEA’s success. It appeals to those of us who can’t stay rooted, who end up moving for work or school (retraining) often, who need cheap, disposable furniture to furnish a cheapened, disposable life. IKEA’s focus on design and modularity is almost too perfect: you are welcome to (indeed, you must) furnish your home with you own unique style and aesthetic, but you may only do so with the prefabricated and highly limited options available to you in the IKEA catalogue. Do you, like millions of others, yearn for the damp streets of Amsterdam pictured in this poster, or for the sun-dappled forest of that one? Do you feel your soul reflected in the nostalgic “hand-crafted” faux-elegance of this bed frame, or the sleek modernist efficiency of that one? Either way, they’re made of the same sawdust and glue.

Prefabricated care in an uncaring world

Let me confess something. When we were exhausted graduate students in Hamilton, Ontario, sometimes me and my then-partner would load ourselves and our school-aged son onto the bus to the Burlington IKEA (which took about an hour, each way) just to get rid of him for an hour. Of course we loved him, but parenting is hard. And anyway, he loved the IKEA childcare centre with its ball-pit, alluringly minimalist Swedish toys and, best of all, narcotic Disney videos that were banned from our home (that’s what happened when you grow up under the tyranny of cultural critics).

After depositing him in the care of some suspiciously over-enthusiastic IKEA employee and receiving the little buzzer that alerts you when your hour of bliss has come to an end, we would wander the show-room examining in detail all the furniture we couldn’t afford to buy and people-watch.

So two cheers for IKEA, for providing such a service to beleaguered parents. But let’s be honest: we know it’s not out of their Scandinavian benevolence. Child care is offered to get us into the store, where the siren songs of a hitherto unneeded egg separator or an absurdly cheap patio set can work their seductive magic.

IKEA works because it is a kinder gentler corporation in world otherwise run by ruthless and abusive corporations. But it’s still unavoidably part of that ruthless and abusive corporate system. We all deserve free, accessible, universal childcare so that parents can escape their children for an hour on the weekends (and vice versa). We also ought to have decent and meaningful work. The items we use should be created sustainably and efficiently. And, in a world as rich as ours, we should enjoy abundance and the ability to chose from a variety of styles and fashions. IKEA offers us a tiny, tantalizing droplet of all these sweet things. But because they are almost nowhere else to be found in our corporate-dominated world, we lap it up and thank them for it.

The reality is that a Sunday shopping trip to IKEA has become one of postmodern life’s small pleasures. But that should tell us a lot about how shitty postmodern life has become in this era of hyper-consumerism and precarious work and life. And IKEA’s business model is based on and helps drive hyper-consumerism and precarious work and life, even if they do it a little more gently than their competitors.

Beyond IKEA

If you’re still here, you’ve clearly overcome the urge to throw whatever paper or device you’re reading this on across the room out of frustration. How dare I criticize IKEA! Don’t I realize they’re doing their best? What the hell is the alternative, professor?

IKEA’s take on Banksy

Well first let me say that a complex and enlightened society (such as ours, allegedly) allows people (especially professors) to bring up social problems without having to pose readymade solutions for a perfect alternative that fit together perfectly like machine-cut IKEA furniture. To demand that everyone who presents a highly complex multi-layered problem automatically have an easy, tweetable solution is unfair and absurd. Your demand for a solution actually has more to do with your desire to avoid the problem than your curiosity (because you’re also just itching to tell me all the reasons my solution won’t work, aren’t you?).

And I get it. I really do. In a world of work and worry, someone criticizing something that gives you pleasure or an escape is pretty hard to take. And in a world filled with corporate devils, a takedown of what appears to be a corporate angel can feel a bit gratuitous.

Well, I don’t have an exhaustive solution, but I will close by noting a few things.

First, IKEA, like all corporations, is the creature of a much larger system of capitalism, specifically of globalized neoliberal capitalism. This means that if a company wishes to be economically competitive with its rivals they realistically have very little room to maneuver in terms of ecological sustainability and workers’ rights. They have no room whatsoever to maneuver in terms of depending on ever-greater consumerism. IKEA can surely do better on a lot of fronts, but currently is relatively better than its rivals. Indeed, being “relatively better” is central to its brand and success. So the problem is not really IKEA but the whole system — the issues I’ve listed here are just symptoms of a deeper social ill.

For that reason, I’m not advocating boycotts of IKEA or consumer pressure. Writing a letter to IKEA will do no discernible good. Neither will going to some big-box competitor. I’m also not suggesting we all stop consuming everything and set to work making all our own tables and lampshades and giving them faux-Swedish names. These are all individualistic solutions. In a society based on individualist consumerism, we naturally gravitate towards such individualistic solutions, even though they will do nothing to solve the underlying problem. Indeed, this is partly key to IKEA’s success: we imagine that all we can do to make our world better is to shop at marginally nicer corporations, like IKEA.

The reality is that the problems we now face demand society-wide solutions and collective action, not individual behavioural or consumer changes.

Maybe we want a local economy that included companies that might produces nice but not overpriced furniture sustainably from local materials, furniture that don’t need to be shipped around the world multiple times over and would last more than a few years. If so, we, as a society, likely through our government, need to make that possible. We would need to provide start-up capital, training and other services. Hopefully it would be a workers’ cooperative, so that the furniture-makers could run their own workplace democratically. In addition to kickstarting such an industry, which might actually create decent work for people, we would need to protect it from price competition from cheap IKEA furniture, which would likely mean taxing IKEA or applying tariffs to their imports. Currently, that’s almost impossible because of various trade agreements and jurisdictional issues, but an enterprising government could figure out a solution, if the will was there.

This gives us a sense of the sorts of shifts that we could think about more generally. Rather than bribing massive foreign corporations to show up in Nova Scotia and either employ us (which seems to pretty much sum up the Provincial governments’ economic development plan) or sell things to us, we could reimagine the economy as a whole, from the grassroots up. We’re not talking about a Soviet-style centrally planned economy, though the government could certainly play a greater role in some areas where markets have been abject failures (eg. Nova Scotia Power). Rather, we could transition towards more worker and consumer cooperatives where we produce more of the necessities and joys of life locally, collaboratively and sustainably, rather than globally, competitively and in ways that are ecologically disastrous.

It may be true that some products are best produced in massified, global ways. New technologies and efficiencies can liberate human beings from some forms of menial toil of mines and factories and produce goods in more ecologically sustainable ways. Thanks to new technology, we humans have previously unimaginable capacities to cooperate and produce what we need on a global scale, and we should take advantage of this potential. But the process should still be guided by democratically determined human values and goals. Right now this process is guided by nothing more than competitive corporations’ lust for profits and based on the presumption of ever-increasing consumerism. It’s a recipe for human and ecological catastrophe.

The details of such a model will need to wait for another time and venue. But there are alternatives. As we celebrate IKEA’s second coming to Halifax, let’s keep it in perspective.

We deserve more.

Max Haiven is co-director of the Radical Imagination Project and an assistant professor at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design where he teaches cultural studies and political economy. He is the author of several books, including Crises of Imagination, Crises of Power: Capitalism, Creativity and the Commons. Currently, he teaches a course on material culture, consumerism and grassroots alternatives at the Halifax Central Library every Tuesdays at 1pm which is open to the public. For more information, you can visit maxhaiven.com

The site for the Halifax local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.