Cancer’s Margins is the first nationally funded LGBT* cancer research project in Canada.

A community- and art-driven project, it has bases in British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and here in Nova Scotia, where teams are collecting the stories of LGBT* cancer patients and people in their support networks. These stories of cancer health, care and support will help to fill a gap in Canadian cancer research knowledge: how to best serve those who identify as LGBT*.

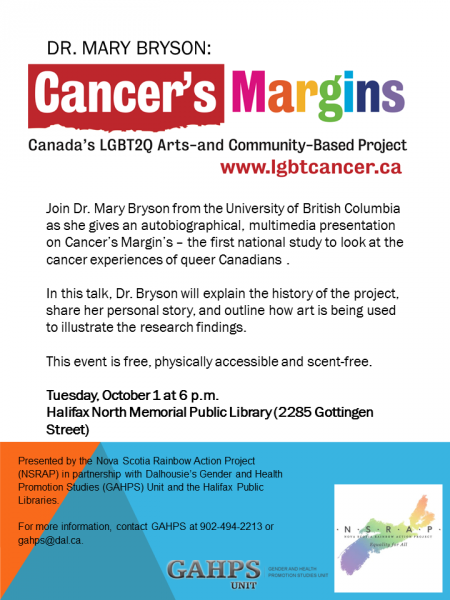

At Cancer’s Margins’ helm is Mary Bryson, a professor of language and literacy education at the University of British Columbia. On Tuesday, Oct. 1, she will be discussing her project at the Halifax North Memorial Public Library. She spoke by phone with the Halifax Media Co-op in advance of the event to describe the complex issues propelling Cancer’s Margins.

Halifax Media Co-op (HMC): How is your project, Cancer's Margins, influenced by your personal experiences?

Mary Bryson (MB): I don’t actually believe that it’s possible for any researcher to know … with any reasonable clarity what it is in their experience that has led them to carry out the work that they are doing …

It is also the case that at different times in my life I have direct experience of identifying as many different things, as we all do. So, I have direct embodied experience, say, of identifying as avidly heterosexual, avidly homosexual, bisexual, queer, trans, kinky, activist, anti-racist, feminist — all of those experiences inform this particular project that I’m doing, Cancer’s Margins. …

It’s also the case that I have been diagnosed at different times both with gynecologic cancer and with breast cancer. My breast cancer was a more difficult, complex diagnosis requiring more surgeries and treatments.

When I was diagnosed with breast cancer I couldn’t help but notice … that there was an astounding lack of queer LGBT knowledge communities, organized around cancer, online, which surprised me a great deal at the time because if we take another really serious disease complex, HIV/AIDS … there’s been a great deal of research on the complexity of HIV/AIDs and culture and gender and sexuality. So it took me by surprise that it was not the case for cancer.

HMC: How are LGBT* people affected differently by cancer than other populations?

MB: It’s safe to say one of the ways of thinking about cancer is in terms of “risk profiles.” And it’s safe to say there are differential risk profiles as a function of sexual and gender marginality.

For example, if you look at trans* youth or trans* people more broadly, there are high rates of smoking. Smoking is a risk factor for lung cancer.

So, there are a whole variety of ways in which literature that provides information about risk will focus on one or more elements that are associated with being LGB or T and that are linked with either behaviours or what public heath researchers take to be relatively stable characteristics of (those) populations …

At the same time, of course, you have to be very cautious. Cancer researchers tend to invariably list not having children as part of the major risk profile for lesbians and breast cancer. But we don’t know, really, who is a lesbian and how many lesbians are having children. So it’s actually very tricky because risk tends to imply causation and that attribution of causation may be reasonable; it may not. …

Data is being collected on Canadians and cancer and those databases about cancer don’t identify gender beyond male-female and they don’t identify sexual orientation. So there’s just a basic lack of really large-scale population data with which we could answer some of these questions. …

HMC: What are some of the difficulties faced by the LGBT* people seeking or undergoing cancer treatment?

MB: I think it’s safe to say there are issues of stigma and discrimination that continue to define and to describe LGBT experiences with health care contexts and health care providers. If stigma and discrimination are still problematically linked with showing up at the doctor’s office; if people are acutely aware of problems of disclosure, which they are; and if good communication is an essential part of good health care, then there is this very tight knot wrapped around the experience of cancer health and care, where people are struggling constantly to communicate with people, and settings, who are using scripts that don’t anticipate their experience, that don’t anticipate their family structure. …

Their (patients’) support networks might look quite different than the support networks of cis-gendered, heterosexual Canadians. … There are elements of who is represented in those support networks; there are elements in terms of the significance LGBT people attach to some particularities about what gender means to them, what sexuality means to them that may be a really important part of conversations that they need to have with health care providers.

Meanwhile, we know … that the average physician gets 40 minutes … of content concerning all of LGBTQ (in medical school). So these care providers really are not equipped to participate in these conversations, which are happening where there’s a huge power imbalance between the doctor and patient. And the patient is dealing with cancer; they’re dealing with a terrible disease, and everyone who is going through diagnosis and treatment is acutely aware (cancer) may kill them much earlier in their life trajectory than they had expected. It’s not really a good time to be struggling to communicate about who your family members actually are, what gender means to you, how the surgery might impact your sense of your sexuality, but we know that cancer patients need to talk about all these things in order to be healthy.

HMC: What would culturally, LGBT* specific cancer care look like?

MB: Basically, culturally sensitive cancer care seeks to find out from the patients themselves a very basic and elementary understanding of what gender and sexuality mean, how they are experienced by the patient, and how it is that that patient would like the singularity of their life experience, of their sense of who they are and their understanding of who their support network is, to inform their care. It turns out it’s not inordinately complex to find out what matters to people about themselves, their sexuality, their gender, their life circumstances and, similarly, how it is they would like to be supported through the experience of whatever the treatment imposes.

HMC: What is the importance of developing knowledge networks between LGBT* cancer patients and members of their support networks?

MB: We know that with online access to health knowledge, we know that people are going online (for medical information), and we know that with any kind of significant issues of medical health that people are more likely to look to learn from knowledge online that represents people and communities that they consider to be like themselves. … And so (because of the lack of LGBT* health websites and forums) there isn’t any way for LGBT to participate to the same degree in what is probably the most important change in the last 100 years in terms of providing open access to medical knowledge, which is going online.

HMC: What can you tell us about the Cancer’s Margins project?

MB: We are doing interviews in urban environments, suburban locations and rural and remote locations. So by the end of two years we’ll have an archive of interviews that represents a very diverse set of stories about the experiences of cancer health, cancer care and cancer support networks that really is in some ways representative of these very diverse communities across the very distinctive Canadian geography of the North, of the big cities, of the rural environments and so on.

And in the second major part of the project, in year three, we will be bringing LGB and T cancer patients together again cross those five provinces in digital storytelling workshops, where in a long weekend, in a kind of micro-documentary boot camp with LGBT directors … Cancer’s Margins interview participants will get to take the basic interview they’ve already done and then tell their story again but tell it more definitively in their own words, in their own terms. They’ll be able to add images, they’ll be able to shoot additional video or tell a completely different story. All of this will enable us, by the end of the third year, to share LGBT cancer narratives on our website that will really add to the archives of the available stories of cancer health experiences that would be relevant to a much greater number of LGBT Canadians than what’s available now.

Cancer’s Margins is looking for participants. If you identify as LGBT*, have been diagnosed with breast or gynecologic cancer, live in one of the five participating provinces and are of the age of majority, you can contact the Cancer’s Margins team to set up an interview. See the project website for details.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.