Halifax Media Co-op

News from Nova Scotia's Grassroots

Silver Donald Cameron: The Canso Fishermen's Strike, Revisited

This blog was originally posted at Small Scales, the excellent East Coast fisheries blog administered by the Marine Issues Committee of the Ecology Action Centre. Another version appeared in the Sunday Herald on July 10, 2002.

Guest Contribution by Silver Donald Cameron.

I had forgotten the beauty of the coastal road from Guysborough to Canso. Sweeping views over a wrinkled, slate-grey sea. Compact, shingled houses. Boys and old men fishing from the bridges. Small boats moored in notches of rock. Wind-stunted spruce. The Queensport Light, shabby and neglected but standing solid and defiant on a rocky islet. Vivid names: Half Island Cove, Lazy Head, Fox Island Main. The road hasn’t changed much in 30 years.

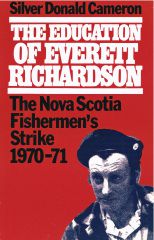

Thirty years ago I drove this highway researching a book. The Education of Everett Richardson: The Nova Scotia Fishermen’s Strike, 1970-71, is now long out of print, though copies are still available at my website. The book told the story of 235 fishermen in Petit de Grat, Mulgrave and Canso whose brilliant, uncompromising battle for justice had electrified the nation, and changed our province forever.

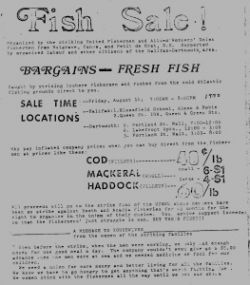

The fishermen were not striking for better wages or working conditions, but — incredible as it sounds — simply for the right to form a union. Under the antiquated laws of the day, fishermen working on industrial draggers were “co-adventurers” with the fishing companies, sharing the risks of each voyage and also sharing the rewards. Since they were not employees, they could not legally unionize.

The draggermen certainly shared the risks; it was not the corporate managers who were drowned, crushed or maimed in winter trawling. But they saw few rewards. A draggerman working steadily might put in 5000 hours a year, for which he would earn $3000 to $5000. Everett Richardson, the Everyman figure at the heart of my book, once worked 62 hours straight, and on one eight-day midwinter trip, he earned $2.01. That’s right: eight 24-hour days, watch on and watch off — for two dollars.

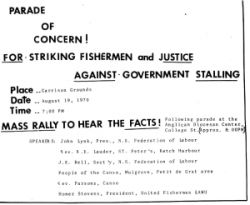

So the Canso Strait fishermen listened keenly to the organizers from the BC-based United Fishermen and Allied Workers Union who appeared in the Maritimes in 1967. But when they went on strike in the spring of 1970, every major institution in the province opposed them or betrayed them — the government, the media, the courts, the business community, even the churches.

The strike’s most dramatic moment came on June 22, 1970. Since the fishermen had no right to organize, they could not legally picket the fish plants. Acadia Fisheries (which owned plants in Canso and Mulgrave) and Booth Fisheries (which operated the one in Petit de Grat) applied to the courts for injunctions banning picketing. But picketing was the only action which could prevent the plants from operating, and was the strikers’ most important weapon. So they ignored the injunction, and the courts promptly cited them for contempt of court.

On June 19, when the defiant picketers from Petit de Grat were sentenced to 20 and 30 days in jail, Everett Richardson was in Ottawa with a union delegation. He gave an unrepentant interview to the Canadian Press. When he faced Chief Justice Gordon Cowan the next week, Everett refused to apologize, or to promise that he wouldn’t walk the picket lines again — and Cowan sentenced him to nine months.

Seven thousand workers walked off their jobs the next day. Miners, steelworkers, papermakers and construction workers downed their tools and went to the fishing ports to walk the picket lines with the remaining fishermen and their wives and children. Three days later, amid growing cries for a general strike, Everett Richardson and his union brothers were released on bail.

In the end, the union fishermen were disgracefully betrayed by the mainstream labour movement, which loathed the UFAWU and its radical leader, Homer Stevens. Flouting the fundamental principle that workers are entitled to be represented by a union of their own choosing, the Canadian Food and Allied Workers struck a deal with the companies. The fishermen woke up to find that they had to join “the CF” or lose their jobs.

But the strike was not a failure. It changed the law, established unionism in the fishery and improved conditions on the boats. It brought together a powerful coalition of resistance — unionists across the country, students, farmers, women, radical priests and journalists, among others. It inspired me to write a book to ensure it would not be forgotten. And just recently that nearly-forgotten book helped inspire some of the young men and women of Canso in the fight to save their town when the cod fishery collapsed.

Those young people organized the Stan Rogers Folk Festival, and this year they asked me to come and read there. So I drove again down that fierce and beautiful shoreline, and I felt the ghosts of those bold, brave men and women around me in the tent as I read aloud from the book I had written for them.

One of Canada’s most versatile and experienced professional authors, Silver Donald Cameron is the host and executive producer of TheGreenInterview.com. He lives in Halifax, Nova Scotia. ‘The Education of Everett Richardson’ was voted one of Atlantic Canada’s top 100 books and is available for purchase here.

The site for the Halifax local of The Media Co-op has been archived and will no longer be updated. Please visit the main Media Co-op website to learn more about the organization.